A Numerical Analysis Of Why Touchbacks Are Still Optimal

A quick foray into the importance of field position, and why even with the new kickoff rules touchbacks are still the best result for the defence.

As we all know, the NFL has recently instituted a new kickoff rule, to try to insert the long-dead play back into the game, but in a more safe way. Recently, retired NFL Punter Pat McAfee, who is a Hall of Fame calibre player (if the Hall were to allow special teams players), and star of the Pat McAfee Show, did a segment discussing the new rule immediately following its first implementation in the Hall of Fame Game. In general, it was a good segment, but it did feature this 55 seconds or so, which I would like to discuss:

First things first, let’s all acknowledge that Pat was a special teams player. He made his money playing special teams, and is recognized as an all time great in the art of special teams. Therefore, he is heavily incentivized to overrate the importance of field position. However, Pat is also a big time NFL voice, and I don’t think he should be allowed to get away with lying to the public like this.

I don’t believe Pat is lying on purpose. After years in the NFL as a special teamer himself, I believe he’s also drank the Kool-Aid and began believing the field position (or where an offence starts when they touch the ball) is more important than it is.

In the above video, Pat is talking about how he doesn’t believe the kickoff will actually change that much, as he believes that even though the touchback has been moved from the 25 out to the 30, teams will still elect to just take a touchback every time, and he believes that the touchback should’ve been moved out to the 35 to try to cull this issue. This is the right argument, but has been made for the entirely wrong reasons. In the end, I agree with Pat that the new kickoff rules will not result in more returns, but let’s get into my disagreements with him on explaining why.

1) “The percentages of scoring a point when you’re at the 35 vs. the 25 are vastly different”

Pat opens up by undercutting his own argument. If a ten yard difference in field position were that important, teams actually would allow returners to return the ball, in hopes of stopping them on the 20 instead of the new touchback line on the 30. If this ten yard difference were critical, it would actually incentivize teams to allow returns by adding more risk to the touchback, but regrettably, it isn’t all that important, and the reason is this graph:

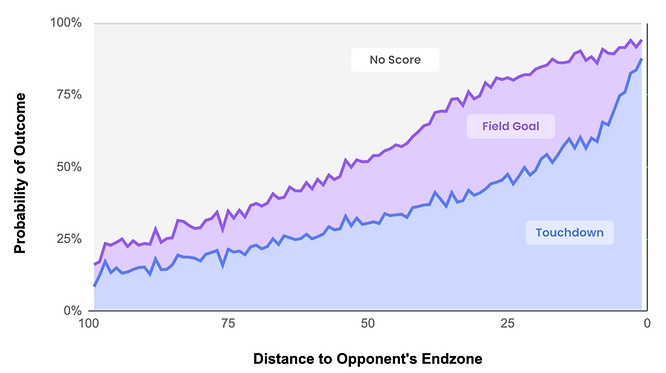

The graph shows the probability of the three scoring outcomes (field goal, touchdown, or not scoring at all) based on your field position. The probability of the current drive ending in a touchdown is the height of the blue line. The probability of a field goal is between the blue and the purple. The probability of scoring at all is these two added together.

This all makes sense. For example, all drives starting way in your own territory (close to 100 yards from the end zone) have around a ten percent chance of scoring a touchdown, and about a further ten percent chance to score a field goal, for a total chance of scoring between 20 and 25 percent as you can see to the left side of the graph. As teams get closer to the end zone, naturally their probability of scoring goes up, all the way down to the one yard line, where the roughly 90 percent chance of a touchdown plus the roughly five percent chance of a field goal gives about a 95 percent chance of scoring.

This is all easy to see, but notice what you didn’t notice.

Where is the massive difference between the 25 and the 35?

The only thing that makes Pat technically correct here, and I suspect what threw him off in this segment, is the statistical anomaly that happens at the 25 yard line.

Look at the above graph, and look at the 25 yard line. You see how there’s a large decrease in your probability of scoring when you get to the 25 that shows your team is dramatically less likely to score on the 25 than either the 24 or the 26? The 25 does not have some mystic power that makes it kill scoring drives. What happens here is that more than any other place on the field, three and outs in the game touch the 25 yard line at some point, mostly from starting there.

This makes the 25 yard line look artificially unattractive according to simple probability charts like this one. Really bad offences that go three and out all the time tend to touch the 25 yard line a lot, which causes the 25 yard line in particular to look really bad in comparison to every other yard marker around it. You can see a mild version of this phenomenon concentrating at the 20 yard line (for touchback punts) as well.

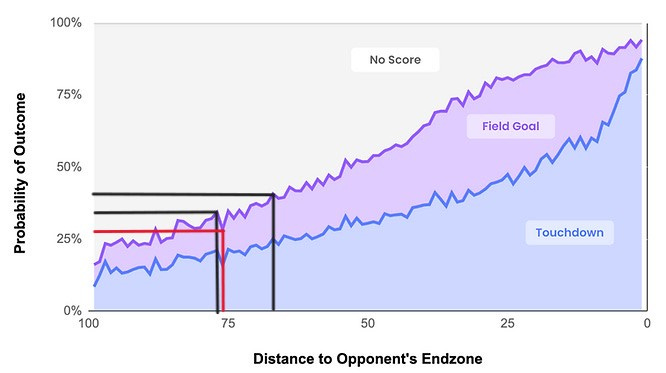

Therefore, for an exercise like I’m about to do, it’s much more prudent to simply look at the probability of scoring from the 24 yard line, and make the assumption that the true probability from the 25 is similar enough that it won’t trouble the analysis. Below, I’ve shown you difference in the two comparisons: comparing the 24 to the 35 vs comparing the 25 to the 35:

As you can see, Pat is technically correct that the 25 is a dramatically worse starting location than the 35, cutting the probability of scoring by about 15 percent. If this were actually the probability of scoring from the 25 yard line, this may work as an incentive to ward off touchbacks. However, by this same image you can also see that (in terms of pure scoring probability) the 25 is a worse starting location than the 24, 23, 22, 21, all the way back to the 15 yard line.

Of course, this is silly. We all know the 25 is better than the 21, but since three and outs tend to touch the 25, that yard marker in particular tends to produce fewer scoring outcomes, which artificially skews a chart like this one. However, this will apply to wherever the touchback line is moved. Therefore, a more neutral comparison is required, which is why I’ve also included the comparison with the 24 yard line, and that’s where you see that this ‘massive’ difference in the probabilities of scoring Pat mentioned doesn’t really hold.

I’m not trying to claim that moving from the 24 to the 35 doesn’t increase a team’s probability of scoring. It does. It increases it by about seven percent. This is a significant increase (anything over five percent is too big to ignore). If a team were to have ten possessions in a game, and start every one of them from the 24, they would be expected to have either three or four scoring events in the game. Starting from the 35 every time in a ten possession game would likely see four or five scoring events.

I know these numbers seem low, but that’s because teams don’t start this far back on every possession of the game. This is strictly an exercise.

The point here is that while four or five is obviously better than three or four, there’s still a big overlap, and I’m going to use Expected Points to put this into even better perspective. Expected Points depends on time left, timeouts left, etc., but in general a first and ten from the 24 yard line will be worth about 0.8 Expected Points or so. First and ten from the 35 will be worth around 1.5.

0.7 points per possession.

Once again, this is very far from nothing. If you multiply this by our ten possession game from above that means you will have lost seven points by the end of the game by giving your opponent such solid field position. A whole touchdown is nothing to scoff at. However, this value gets chipped away once you realize that kicking off all ten times means you’ve likely run away with the game already. If we say you kick off six times, then the value lost to the theoretical kickoff touchback to the 35 is only 4.2 points per game.

4.2 points is just not that much when it’s divided over the course of a whole game. Over the course of an entire NFL game this is a very easy total to make up elsewhere. For instance, if you win the turnover battle you’ve likely made up this entire gap, and I’ve already written an article detailing why the turnover battle isn’t all that important either.

Considering offences in the NFL can generate over ten points above expected on the regular (the best offence in 2023 averaged about 12 every game), you can begin to understand why surrendering 4.2 points in a game to field position is less important than people like Pat McAfee think it is.

Teams for years have been choosing to simply surrender these points by kicking every ball through the end zone, entirely nullifying any chance at anything bad happening in a kickoff return, and they’re not going to stop now. Therefore, Pat is entirely wrong about this, although for the sake of the kickoff he and I both wish he was right.

Let’s move onto the second argument.

2) “A 35 yard penalty will force people to kick it into the landing zone”

I like where he’s going here.

He was sly about slipping this one in there. He said it with such conviction that you likely believed his side without thinking twice about it, and were much more likely to advocate for Pat’s rule change after hearing it. However, this assertion caught me off guard because I’ve been spending the last month and a half of my life pouring over play by play data from Trent Green games (check out my Trent Green series), where teams regularly kick the ball out of bounds (in essence, taking a touchback at the 40) in fear of Dante Hall.

We just got done talking about how the 35 vs the 25 is not as important as it’s made out to be, and there is precedent in NFL history of teams electing to just give the opponent the 40 rather than face an elite returner, so what makes the 35 so special that teams wouldn’t just take touchbacks from there?

If some theories about the new return rule are right, and it’s going to turn every returner in the game into 2006 Devin Hester, then let’s do the analysis.

2006 Devin Hester did more damage on punts than kicks, but still turned ten percent of his kickoff returns into touchdowns, in addition to allowing the 2006 Chicago Bears to have an average starting field position of their own 33, which is very far forward. However, as with any kick returner, there’s going to be a lot of duds, so we have to assign a real probability to a totally nothing return, which for this purpose I’ll say gets to the 20 yard line (likely too short with the new rules, but let’s work with it).

So, if every returner in the NFL is 2006 Devin Hester, ten percent of their returns will be touchdowns. I’ll assign a probability of half to an average return (which for our purposes will be the 33 yard line) and a 40 percent probability to a dud on the 20 yard line. We already know that giving the opponent the ball on the 35 with a touchback gives them abut 1.5 expected points straight up. No questions asked. What is the expected value of a return from 2006 Devin Hester?

A touchdown gives seven points without any further input. An average return gives a very slightly worse outcome than the 1.5 Expected Points from the 35. I’ll use 1.45 for this analysis, and the dud return gives the Expected Point value of first and ten from the 20, which is about 0.6.

Multiplying these numbers by their probabilities to generate an Expected Point value of a return generates the following result:

0.1*7 + 0.5*1.45 + 0.4*0.6 = 1.665 Expected Points per return.

If you’ll notice, this is more than the 1.5 Expected Points your opponent gets from just giving them the ball at the 35, meaning that even if the rule is changed to make the touchback the 35 yard line, touchbacks will still be optimal. Even if the returners are slightly less good than 2006 Devin Hester, this result stands a good chance of holding, because I’ve likely overestimated the probability of a really bad return under the new rules.

This lack of ability to disincentivize the touchback is what killed the kickoff in the first place, and I’m not sure the new rule has fixed it, because I think Pat is right that touchbacks need to be moved even further up the field to prevent touchbacks from remaining the optimal outcome from the perspective of the defence, although I believe he is not extreme enough.

In my opinion, anything short of treating the end zone as out of bounds (and therefore moving touchbacks to the 40 yard line) will fail to change the prevailing opinion among special teams coordinators, and data geeks like myself, that touchbacks on kickoffs are the optimal outcome. Moving touchbacks out this far may not be worth it, and may make it optimal for the returner to just let the ball roll into the end zone and down it there, so quite frankly, I cannot devise a way to save the kickoff return in the NFL.

In sum, field position is not as important as its made out to be by football players and pundits. Coaches figured this out years ago, and this is why the kickoff died, because the benefits of being more likely to keep the opponent to a slightly longer field are trumped by the downsides of potentially giving up a big return. In my opinion, the new kickoff rules have not fixed this problem. I don’t know if any set of kickoff rules can fix this problem, because no risk touchbacks are just such a good outcome for the defensive team.

What absolutely must happen is the touchback being moved out beyond the 30 yard line, because if it remains at the 30, I remain in agreement with Pat McAfee that defences are absolutely correct to just not allow the return at all and take their chances with the 30 yard line.

This is sad, because I love kickoff returns, and I don’t really want to see teams consistently getting the ball at the 35 for free, as it will serve as a free boost to scoring for a league that doesn’t need one. However, I can see no alternative (other than perhaps moving the touchback to the 40, but that may have its own unintended consequences).

I was hyped for these new kickoff rules, but I’m not hyped anymore. I think the play will continue to be the boring touchback marathon that it’s been for years.

Thanks so much for reading.