Historical CPOE: Results and Takeaways

Discussing my project to project CPOE into the NFL's past, presenting the results, and telling some interesting stories.

Welcome back to my Sports Passion Project everybody, where I’ve been advertising my historical CPOE project for better than a week over on Substack Notes, and it’s finally here.

This idea began with the Matthew Stafford trade rumours, when myself and several friends began discussing the idea of a ‘system QB,’ or for a more concrete definition, a man on the extreme bad end of the spectrum ranging between a QB carrying his offence, and his offence carrying him.

I speculated (correctly) that no team would be willing to trade for Stafford, because when you look up ‘system QB’ in the dictionary, Matthew Stafford is who you ought to see in my opinion. In both Detroit, where the offence got better after he left, and in Los Angeles, where the offence was better before he got there, it’s been made clear that he’s been holding his teams back.

The primary reason for this is his career CPOE figure of -1.3. Matthew Stafford has made a career out of getting workable results (usually in the teens in the EPA/Play rankings), without the requisite skill to do so. Put simply, he can’t throw the ball accurately, and never has been able to throw the ball accurately.

This ‘system QB’ train of thought got me thinking of a broader QB measure, one that doesn’t necessarily measure results, but measures how good a QB is, individually. There would only need to be two components, because there are only two things that a QB needs necessarily to be good at to succeed. He needs to be able to throw the ball accurately, and he needs to be able to not get sacked in the process.

Measuring the ability to not get sacked is simple. One can just use a QB’s sack rate, which is historically the stat the QB holds the most individual responsibility for. However, passing accuracy is trickier to nail down as you go back in history. From 2006 onwards, it’s easy. One can just use Completion Percentage Over Expected (CPOE) to measure passing accuracy.

CPOE is a statistic that gives every individual throw a measure of difficulty, based on distance of the throw, directionality of the throw, down and distance, under a roof vs outside, and a myriad of other factors. Once this is done for every one of a player’s throws, they are all aggregated together into an expected completion percentage. What percentage of passes would an average QB be able to complete, with the exact same collection of throws, and their associated difficulties?

With modern NFL standards, depending on play style, some QBs can have an expected completion percentage as high as 70, if they throw exceptionally safe passes all the time. Others can have expected completion percentages as low as 64, if they’re constantly throwing the ball down the field.

CPOE is simply a subtraction of a player’s expected completion percentage from their actual completion percentage, giving a measure of how many throws they completed that an average QB wouldn’t have, or in the case of a negative result, how many more throws an average QB would’ve completed that the QB in question did not.

Taking this back to the Matthew Stafford example, his -1.3 percent career CPOE, on 8166 career passing attempts, means the NFL average QB would have 106 more completed passes in his career than Matthew Stafford has. If we turn this around, and look at the most accurate QB that’s still active, Russell Wilson, his career CPOE of positive five percent on 6001 career pass attempts means the average NFL QB would have 300 fewer career completed passes than Russell does. At his career average of 12 yards per completion, this means that an average QB would have 3600 fewer career passing yards than Russell Wilson has right now.

As you can see, accuracy adds up.

The reason CPOE is my favourite accuracy metric is that it takes into account throw difficulty, which regular completion percentage cannot do. Simply looking at Russ’s 64.7 career completion percentage, nobody would conclude that he’s the most accurate passer of his era, but once we take into account that the average throw over the course of his career is extremely difficult, the result becomes clear.

However, throw depth did not begin being tracked until 2006, meaning there cannot be a measure of CPOE before that season. This leaves us without a reliable accuracy measure as we move backwards through time, because I have very little respect for standard completion percentage. It’s too correlated with throw difficulty. Aidan O’Connell attempts systematically easier passes than Josh Allen does. As a result, his career completion percentage is approximately equal to Josh’s. Does that mean he is just as accurate?

Not a chance. We can all agree on that, so we can all agree that the usefulness of raw completion percentage is limited.

This means I was left in a box. I could reliably measure passing accuracy going back to 2006. I could predict it quite closely going back to 1999 (the beginning of the play-tracking era) using variables present in NFLFastR that aren’t throw depth, but before 1999, I had nothing.

I had nothing, but I still wanted to measure QB skill. Nothing would not do.

So I decided to try to predict past CPOE myself.

Coming into this project I had two goals. First and foremost, this CPOE measure I was creating must correlate loosely, but not exactly, with results. In general, a more accurate passer means a better player, and better players generally get better results, but Geno Smith has finished with a CPOE better than five, yet remained outside the top 15 in the EPA/Play rankings, twice just in the last three years. Players with below average accuracy get into the top ten in EPA/Play all the time, so this correlation between accuracy and results must exist, but cannot be especially strong. That was number one.

The second goal was that this could not just be a rescaled completion percentage ranking. If that were the case, I could just use completion percentage. However, this correlation is allowed to be a lot closer than that between accuracy and results. For example, numbers one, two, three, and four in the 2024 CPOE rankings are numbers two, four, one, and three respectively in 2024’s raw completion percentage rankings. Numbers 44, 43, 42 (the worst three qualified finishers) were exactly 44, 43, 42 in the raw completion percentage table.

Therefore, I don’t mind the correlation between my estimated Completion Percentage Over Expected and raw Completion Percentage being extremely strong, as long as it’s not one to one.

The model that best ended up achieving these goals was one too simple to even bother discussing in great depth. It’s a simple projection of the player’s expected completion percentage from a nonlinear combination of the league’s average completion percentage in the particular season, the player’s yards per completion figure (as a proxy for throw depth), and the player’s own completion percentage achieved that season (creating the implicit assumption that completed throws are generally easier than incomplete ones).

This simple nonlinear combination is able to predict expected completion percentage with an R-square of 73 percent, and subtracting raw completion percentage from this projected expected completion percentage to generate a theoretical CPOE figure tracks real CPOE with an R-Square of 80 percent.

This is to say that, when predicting a real CPOE value, 50 percent of the time my model can predict it within one percent. 80 percent of all observations are predicted within two percent, and virtually all observations are predicted within one standard deviation (the standard deviation of CPOE is 3.87).

This model works well in almost all cases, but there is one flaw. People who spend entire careers attempting extremely difficult passes, without great receivers to throw them to. In the CPOE era, this fits Russell Wilson to a tee. His career aDoT is closer to his career Y/C than any other player, due to the Seahawks generally not having any YAC for him. This tricks a model built strictly on statistics available in 1970 into thinking his throws were shorter than we actually know that they were, making him alone account for six of the model’s 16 biggest absolute residuals, each and every one of them underrating just how accurate he was.

In general, I have faith in my CPOE projection, but be weary when it comes to the ‘deep throws, bad receivers’ archetype. Note this only applies to people whose deep throw depths translate into shockingly low yards per completion figures. People who throw deep, and get sensible results out of it, are accounted for perfectly fine here. It’s just those who constantly chuck the ball deep, and are constantly let down by their receivers not getting catch and run touchdowns, who end up being penalised.

Thankfully, this is not a very common archetype of player. In the CPOE era, there are only two people (Russell Wilson and Tyrod Taylor) who have spent whole careers playing like this, which is why these two by themselves account for better than half of the model’s 16 biggest misses. If we assume this same two players per 19 seasons ratio all the way back to the merger, I can conclude that this won’t harm our understanding of NFL history in too dire of a fashion.

This CPOE model is only a first revision. Should I go back and revisit this (which I likely will), I’ll go back and see what I can do about ‘deep throws, bad receivers’ types.

Now that all of that has been discussed, now we’re able to get to the good stuff.

Who wants to see some results?

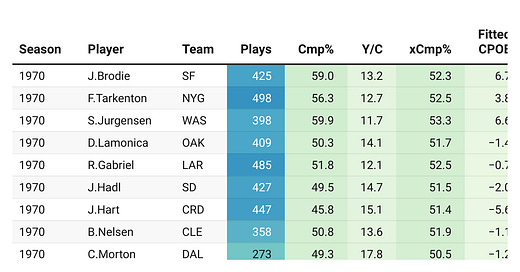

Below is a table featuring every qualified QB season since the NFL merger. On it is every player’s play count, their completion percentage, my fitted expected completion percentage value, and their associated fitted CPOE value, until 2006, when the values switch from the projected CPOE figures to the real CPOE figures.

(P.S. I know the heat map doesn’t work. It wasn’t supposed to work. I only used it as a form of vertical striping to delineate the columns from each other)

Here are some tips on how to navigate this table:

The default sort is my QB tier list for every season up until 1999, where the sort switches to the EPA/Play rankings, for a more objective results measure. This is to prove my first point, that the correlation between accuracy and results is general but not exact. On this front, I would say I was staggeringly successful. Correlation between pass accuracy and results in 1970 is approximately just as tenuous as it is now.

This is one thing you can do with this table, but I’ve structured it such that you can do several things with it. If you want to see the best CPOE seasons ever, simply sort the whole table by fitted CPOE by clicking the column label. If you want to see the worst, click it again. If you want to survey the CPOE rankings in any particular season, simply type that season into the search box.

Give it a try. I personally like ‘1998’ as a first thing for somebody to try searching, a season where the battle for most accurate passer in the NFL is basically a four way tie between two likely suspects and two extremely unlikely ones, plus you get a look at Peyton Manning being worse than league average in terms of passing accuracy, a pattern that does not persist for very long.

Speaking of players, you can analyse player career paths using this table also, by simply searching the player’s name, with the specific format of the first letter of their first name [dot] their entire surname, with no space, as in ‘P.Manning.’ For those who follow me on Notes, you guys know that ‘A.Manning’ (as in Peyton’s father Archie) is quite the search on this table, as his journey from not being able to throw the ball accurately, missing the entire 1976 season reworking his throwing mechanics, and coming back as an extremely accurate thrower of the football is quite the interesting career path.

There are several interesting career paths one can analyse on this table. I will give you one further example. In addition to Archie Manning, try typing ‘K.O’Brien,’ and seeing what you find. Once you see his accuracy numbers, you likely won’t need me to tell you exactly when he messed his shoulder up.

You can even type in a team name if you want to. For instance, try typing in ‘CHI’ or ‘CLE,’ and looking upon the years and years of misery they’ve had at the QB position. Alternatively, you could type in ‘SD,’ if you want to look upon a team with a generally good QB history.

I’m fairly proud of myself for designing such a versatile piece of data visualisation as a complete novice. It may not look especially good, but you can analyse seasons. You can analyse players. You can even look through team histories if you’d like. Let me give you some examples on how I’ve used this table already to help with my specific type of analysis:

I mentioned Ken O’Brien before, but I seriously want you to look at him. This guy is remembered as more bust than not as a first round QB draft pick. However, he led the NFL in fitted CPOE in both 1985 and 1986, and had even gotten his sk%+ up to 101 in 1986. As far as I’m concerned, this was one of the best QBs in the NFL, before shoulder injuries took it all away from him, as he never could throw accurately on a consistent basis at any point after 1986.

There are not many Ken O’Brien historical defenders out there, but maybe just maybe this table will create some. In fact, it’s already created one out of me, and he’s not the only player. I used to think of Ken Stabler as an undeserving Hall of Famer. After this experiment, I do not think that anymore. It’s not all positive (I thought a lot more of Terry Bradshaw yesterday than I do today), but it’s all very informative.

Additionally, like any good data researcher, I immediately used this new data to go back and begin proving or disproving my old assertions. Specifically, I went back to my ranking of One-Off QB Seasons. In that list, I specifically named Steve Pelluer, Ty Detmer, and Craig Erickson as players that played so well in their limited playing time that it became egregious that they never got more. How do those assertions look now, in light of new data?

Steve Pelluer comes out smelling like a rose even still. His CPOE figures are almost exactly in line with his results, which is generally above average, but not quite top ten worthy. Nevertheless, this was a starting level NFL player. No question about it. He just got himself in the Justin Fields position of his team having the number one overall pick through no fault of his. Dallas drafted Troy Aikman, and Steve Pelluer made three further NFL starts, which even with the benefit of new data, still looks to be a galling decision on the part of the league.

Ty Detmer looks to be a bit less sure than Steve, but it remains fact that he got himself 577 DYAR (11th), 10.2% DVOA (12th), on a 1.6 fitted CPOE (8th) in 1996, and was never given a sample bigger than 300 plays ever again.

As for Craig Erickson, the new data indicates in this case that the league likely made the right choice. He got top ten results, but on a fitted CPOE of -0.9 and a sk%+ of just 107, it was never going to happen twice. This was likely a below average player, even with his very good 1994 results. I feel less bad than I used to about him never getting to start again.

You’re reading my Sports Passion Project, so of course the first thing you see when presented with this treasure trove of new data is a call for justice on behalf of Ken O’Brien and Steve Pelluer. If you expected any different from me, you mustn’t know me very well, but from here on, you won’t be getting this data from me. It’s yours now. You can do anything you want with it. The world is your oyster.

However, there is one more table that I will make on your behalf.

This is the table of career CPOE leaders since the NFL merger, among all players who touched the ball at least 1000 times in and after 1970. On this table are the years that the player’s post-merger career spanned, the team they took the most post-merger snaps with, and their career CPOE total.

As a Jaguars fan, I love hitting people with the fact that David Garrard has a higher career CPOE than Tom Brady. I’ve been doing this for years, as it’s a nice little way to poke fun at the Tom Brady stans, wrapped in an informative example of how passing accuracy is not everything, but I wonder how those same Tom Brady stans would react if I let them know that Tom was approximately as accurate as Ken O’Brien, meanwhile their perpetual whipping child Peyton Manning is in the top ten most accurate passers of all time?

Likely not well.

When I started this passing accuracy experiment, I did not expect ‘Steve Young is the most accurate era-adjusted passer in NFL history, and it’s not even close’ to be the result that I came to, but thinking back on it, I suppose I should’ve predicted this. He did lead the league in completion percentage in 1994 by six full percentage points, and led in 1997 by six and a half, after all. He was doing entirely different things than the rest of his league were able to do.

The 1990s are a really weak decade for QB play. Probably the worst decade the post-merger NFL has to offer. When Joe Montana and Phil Simms did not qualify from 1991-1993, Jim Everett got stuck on some horrendous Rams rosters, Boomer Esiason declined, Bernie Koser declined, and Neil Lomax retired, there just was nobody to fill the gap left behind by the greats from the late 80s. Steve Young, Troy Aikman, Jim Kelly, and John Elway tried their best, but people like Brett Favre were not ready yet, and there just weren’t as many names rising as there were falling.

The 80s turning into the 90s is the only time in league history that we saw QB play get worse, and stay worse for a sustained amount of time. QB play would not reach the level of the late 80s again until the league changed the rules of the game in 2004 to artificially bring passing back to that level, once it became clear that it was never naturally going to get back, and Steve Young (whose prime ran from 1991-1998) was in perfect position to take advantage of this bad league, from the perspective of a stat that measures accuracy vs the league’s average QB.

Comparing against such a bad league average QB surely helps Steve’s case, but take note that there are other players whose primes centralised into this 1991-2003 dead zone, and Steve is the one that broke over a full percentage point ahead of the pack. Troy Aikman didn’t. John Elway didn’t. Kurt Warner got the closest, but he didn’t either. Steve Young did. In terms of accuracy relative to his offensive environment, there are few close enough to the back of Steve Young to even see his dust. This is a big part of the reason that I’m a Steve Young over Joe Montana guy, and have been for years.

That’s the big story from this table, but there are others.

Shout out to the more extreme offensive environment of the 1970s, where Bob Berry put up a 5.7 CPOE from 1970 to 1972, before falling out of the league entirely, because his career sk%+ of 59 had become too much to deal with. Jeepers creepers. Put Bob Berry’s arm on Anthony Richardson’s legs, and you’d have the best QB of all time. Instead you have, well, Bob Berry and Anthony Richardson…

Passing accuracy is not everything. Even in an article all about passing accuracy, we must remember that.

Fran Tarkenton gets remembered a lot for his rushing ability, but these results seem to indicate that his ability to throw the ball is not revered anywhere near as much as it should be. His 59.7% post-merger completion percentage is nothing special on the surface, but playing mostly in years where the league average completion percentage was between 51 and 53, this makes his accuracy mightily impressive, in addition to all the scrambling he did.

There are countless stories like this that you can learn yourself by pouring through this data. Feel free to talk to me in the comments about any of them that you may happen to find interesting (John Elway being a negative CPOE guy for his career, anyone?), but I’ve been working on this project for weeks, and I’m done with it for the moment. The data cat is out of the bag. Now it’s up to you guys.

I’m looking forward to see what you make of it.

Thanks so much for reading.

This is great. I could spend a lot of time just looking at this data and seeing what pops out. Looking at Elway for example, for his first several seasons it's almost like his estimated CPOE is negatively correlated with team success. The first season he had a positive CPOE was by far the worst record the Broncos had during his career. (Speaking of his career, that -8.4 his rookie season was a really deep hole to climb out of.) Obviously there's a lot more to a team than just good QB play, but I find that really interesting. Was Elway forced to throw better because his team was losing?

I'm going to have to think some more about whether I agree that CPOE and sack rate are sufficient to define a QB's tangible skills. One aspect I'll push back on a bit is the suggestion that receiver quality is the explanation for why a QB wouldn't see good YAC on his throws. That's part of it, but the QB decision making process is a factor too. Take Wilson for example. He often chose to throw (accurately) into situations where the receiver had no opportunity to get additional yards, where if he had thrown the ball sooner or to a different receiver the YAC would have been there. It's also a matter of where on the field Wilson would choose to throw. He rarely targeted receivers over the middle where they could make a move. He'd hit them on the sidelines where they could be forced out of bounds.

Anyway, this is excellent work. I'm sure a lot of people will find this incredibly useful.

Warren Moon has one of the lesser known great peaks. From 89-92, he had projected CPOE of 4.1, a Sack%+ of 113, and a NY/A of 116. He also claims back to back number 1 slots on your QB tiers. His only weakness was fumbling (0.81 fumbles per game).

It is fitting to see Stafford and Eli both at -1.3 career CPOE. Page 9 is my favorite. Andrew Luck has the same CPOE as Mitch Trubisky, and CJ Stroud is in between Justin Fields and Alex Smith. Imagine people trying to rationalize that.