"Let Brock Bye" And The Death Of Motocross's Innocence

The story of Bob Hannah, Broc Glover, and the team order that killed a sport.

Welcome back to my Sports Passion Project everyone, where today I’m going to be talking about the health of a sport, and how motocross shot itself in the foot in a way it’s never recovered from.

Sports are a refuge for many people, one of the final places on Earth where what you know is still more important than who you know. A strict meritocracy in a world where merit feels as if it means less and less each day. There’s an innocence to sports (both watching and playing), because they haven’t been corrupted by the real world. That is a key part of the appeal, and maintaining that innocence is a crucial part of the being of a sports league.

Every sport that’s ever had to deal with a decline in popularity has dealt with a preceding loss of innocence. MLB had to deal with being the first league to have its players unionize, bringing collective bargaining into North American sports, exposing baseball for the business it’d always been, and in so doing, tainting its innocence to many fans.

Baseball soon lost its position to football as the undisputed number one sport in North America, with the owners successfully forcing the players to go on strike in 1994 pounding the final nail into the coffin of baseball’s innocence. Baseball has never recovered. Baseball never will recover.

The sport with the second most egregious fall from grace is NASCAR racing, which rose to be the second most popular sport on the continent with baseball’s repeated shooting of its own feet in the 1990s. However, instead of learning from baseball’s mistakes, NASCAR chose to follow in baseball’s footsteps by repeatedly twisting the blade in the corpse of the purity of their sport. It’s not a coincidence that NASCAR’s decline in popularity almost exactly coincides with the time they began throwing fake debris cautions, in September of 2004.

The NBA had to deal with a serious innocence problem in the 1970s and 1980s, when the league had the image of being populated by cocaine addicts and other seedy characters. David Stern was brought in to fix the league’s innocence problems, and the NBA has been on the rise ever since.

Roughly equivalent to the popularity of the NBA in the 1970s and 1980s was the NHL. However, as the NBA was fixing their league’s innocence problems, the NHL owners were successfully forcing their players to go on strike in 1992, and locking those players out in 1994. This repeated massacre of the purity of the game is the reason the NHL fell from just behind the NBA to just ahead of MLS in terms of popularity.

None of these happenings were natural. These ebbs and flows in popularity are all associated with the general perception of the purity of the game. Fans don’t want to deal with lockouts. They don’t want to deal with player strikes. They don’t want to feel as if their watching dollars are helping players fund their cocaine habits, and they don’t want to feel like they’re helping John Fisher move to Las Vegas.

Innocence is a highly underrated element in the popularity of any sport. The less fans have to think about the inner workings of the sport (owner vs player, owner vs fan, manipulation of results by the league, etc.), the more they can think about the games themselves, and the more popular the league will be.

This doesn’t just apply to sports either. The booming hippie subculture was in large part killed off in one day (‘the day the music died’) in 1969. The Canadian Progressive Conservative party killed itself off with one poorly thought out political attack ad in 1992, making fun of disabled people. There are countless other examples, all illustrating the point that innocence (or purity) is a key factor in continued popularity.

The last time I wrote about dirt bike racing on my Passion Project, I told you several things about the sport of American bike racing. I felt no need to go into them in any detail, because they’re simply facts.

I said things like: nobody cares about motocross. All the money is in supercross, and if they could pick only one, every rider on Earth would choose to be better at supercross.

You probably didn’t have any second thoughts about these facts, and just took them as given. That’s okay, because I consider myself a trustworthy source, but writing these sentences made me wonder why this is. How come indoor racing is so much more popular than outdoor racing? After all, motocross was invented first, which should give it a perpetual head start in popularity over its younger brother, so how did it come to be this way?

Let me tell you the story of how motocross racing lost its innocence.

The year is 1977, and at this point, MX racing is still a relatively young sport in America.

To the best of our knowledge (motocross scholarship is not of the highest quality, compared to other sports) motocross racing as we know it today was invented in Britain, with the first meet resembling modern motocross being termed the Southern Scott Scramble, and taking place on March 29, 1924.

For its first 25 years of existence, the new sport would be dominated by the British. However, instead of scrambling, the name that stuck would be the French-sounding word motocross, leading historians to mistake the sport as having been invented in France for years.

Such a sport did not exist yet in America. American dirt bike racing was mostly conducted on flat dirt tracks with big chunky 500 or 650cc bikes, instead of the nimble and agile 250cc European bikes. However, in the post-WW2 years, American culture began to change. A country that’d (mostly) successfully resisted foreign cultural incursions for its first 170 years of existence was all of a sudden stocked with young people who had spent their formative years either in Europe or Japan themselves, or thinking about their parents or siblings that’d been sent to Europe or Japan.

These young people were more amenable to foreign cultural influences, and while much more important aspects of American society were adopted in this time as a result, I’m focused on the rather niche European cultural import of MX racing, which began in America with Edison Dye and his Flying Circus.

Edison Dye was merely an entrepreneur, who wanted to sell more motorcycles (he was a North American Husqvarna distributor), but ended up becoming the single most important person in the history of American motorcycle culture, mostly by accident. In a brilliantly designed publicity stunt, Edison brought the 1966 world champion, Torsten Hallman, to run races all over America in the world championship offseason.

There’s no better way to get Americans into a new sport than this display of a Swedish rider on his Swedish Husqvarna effortlessly winning by full laps over American riders on their American bikes. However, American riders cannot be bred overnight, so Edison spent the next few years bringing all the top Europeans to America in their offseason to compete for the benefit of the American audience.

Once the AMA (American Motorcyclist Association) saw this, they knew they had to put a halt to it. Edison was an ‘outlaw,’ meaning his races were not sanctioned by any recognized body. This would not do, so in 1971 the AMA strong-armed Edison’s series away from him, and it would become the Trans-AMA series from then on. However, this is not the series I’m going to be talking about today.

While the Trans-AMA offseason series is what popularized motocross racing in America, the fans needed some place to watch racing in the on-season. Therefore, the early 1970s saw the invention of the AMA national championships (the 2001 version of the national championship is what was touched on in my previous motocross article).

As some American riders finally came along to challenge the Europeans, the popularity of this new sport was shooting to the moon, with there being reports of some meets drawing up to 40000 people, which for a sport that in 2024 draws significantly fewer people than that (putting it mildly), is moon landing levels of popularity. However, like I said, the iceberg is coming. The 1977 season is going to change all of this forever, and set the sport on a path to the level of popularity (or lack thereof) that it has today.

Let me tell you that story.

There are three main players in the 1977 125MX season. The first (and by far the most important) is Bob ‘Hurricane’ Hannah. Considering 1977 is only the beginning of Bob’s story (he’s only 20 years old), we don’t know very much about how it’s going to transpire. However, here is what we do know.

Bob is a working class kid born in the Mojave desert in California. He grew up riding, but mostly focused on traditional American-style racing, because his did believed motocross was too dangerous. Therefore, Bob has to wait until 18 years old to get a taste of MX racing. It’s an understatement to call this a late start, but Bob is a natural.

Borrowing a ČZ from a friend, Bob so dominated his only amateur class race that organisers told him (not being a minor like most of the amateurs) that he would have to move up to the pro class if he wanted to race anymore. However, Bob didn’t have any money, and this borrowed ČZ could only go so far, so that one win is the only win Bob would get in 1974.

By the time the 1975 season rolled around, Bob had saved enough money from his day job working as a welder to buy himself a Husqvarna that he could go on a real privateer campaign with, and he dominated the local scene in California, most famously winning 18 races in ten days, because there were no rules against competing in multiple classes at this time.

Still, at the time Bob was thought of as a local California pro. A great local pro, but not a National calibre rider. That’s why Yamaha was able to scoop him up for just $1000 per month to race for them in 1976 on the national level, because Suzuki (Bob’s preferred destination) was willing to offer only $700 per month.

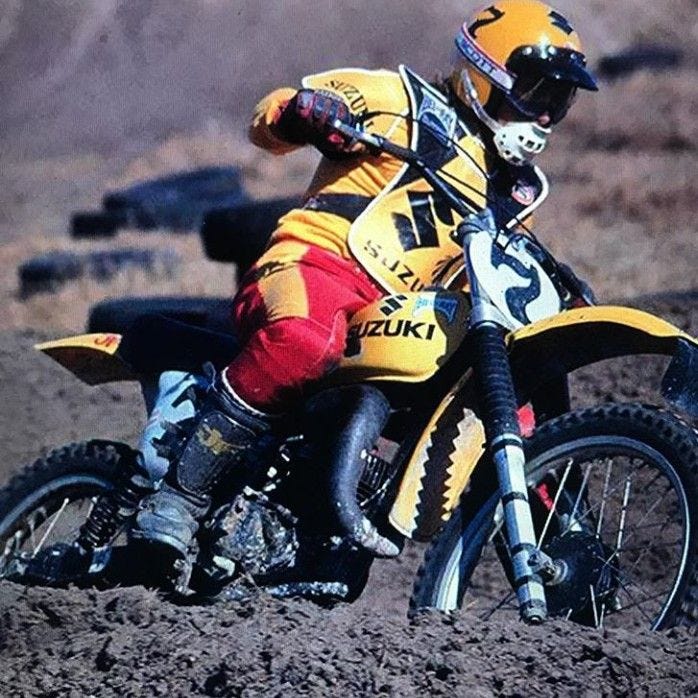

It’s not reasonable to expect a team to look into the future and know what this local California pro is going to become (which is the second best rider in the history of motocross, behind only Ricky Carmichael), but I bet those Suzuki executives spent years wishing they could’ve found an extra $300 per month to give to Bob. Instead of Bob Hannah, Suzuki would end up with Danny LaPorte.

More on him later.

Bob would blitz the field in 1976, and ruin the plans for Marty Smith to be MX racing’s big American star. Marty had a boyish face with a nice smile and came from a bit of money, being raised in San Diego, but also had the skill. He had won each of the previous two 125cc championships. This meant that he was seen as marketing gold to the executives at the time trying to promote this hot new sport.

Bob had no sympathy for any of that.

He viewed this as class warfare. The San Diego pretty boy versus the California desert rat, and Bob buried Marty in the ground, winning the championship by 87 points. That’s over three full races’ worth. This is where he gained the nickname ‘the Hurricane,’ going round and round so fast and leaving such absolute destruction in his wake.

Going into 1977, Bob truly wants to burn the motocross world down, as he wins the premier class 250cc supercross championship before the outdoor season starts, and commits to running all three outdoor classes (125cc, 250cc, and 500cc). Yamaha says okay, but only if he commits to run 125cc rounds should there be any scheduling conflicts, and the AMA (terrified by the idea of Bob winning every championship) responds by creating a scheduling conflict, ensuring that Bob cannot win both the 125 and 250 championships.

Bob is never really a factor in the 250 class as a result, but in the 500cc class he gets into another fantastic shootout with old rival Marty Smith that I don’t have the time to cover here. Just keep in mind that as this story is happening, Bob is also fighting for another national championship on the side.

To cover Bob’s escapades in the 125cc class, I must fill you in on his two main competitors.

Bob’s stiffest competition going into the season is sure to be his Yamaha teammate, Broc (not Brock) Glover.

Broc is another man who (much like Bob) is going to do exceptional things in the motocross world, but as of 1977 hasn’t done them yet. It’s tough to talk about Broc Glover in 1977, because by all reports he was not yet the egotistical, braggadocious, entirely insufferable, blonde haired golden boy that he will become once he really hits his stride starting in 1979. However, there is so much dislike for Broc Glover in general that nobody really cares to remember what he was like before then.

Broc’s story is a lot like Marty Smith’s story. Born in raised in San Diego, Broc became the first member of the ‘El Cajon zone,’ referring to the fact that his area of California seemed to produce motocross talent as if they grew on trees. Surprised by a gifted motorcycle at 15 years old (by a father who previously hadn’t been in the picture), Broc became enthused, and at the age of 16 years old ran in that same 1976 season that saw Bob Hannah establish himself on the scene.

Impressed by this performance, Yamaha brought Broc in to be Bob’s support rider for the 1977 season. However, Bob Hannah and Broc Glover could not warm up to each other if they were cremated together. Once again, Bob interpreted Broc’s San Diego background and his long blonde hair and his golden boy persona as an affront to everything Bob enjoyed about life. As a result of this fractured relationship, trying to put Broc into a support rider role was never going to work.

The story of the 1977 season can truthfully be told with just these two characters, but in order to get a full understanding of what’s going on, we must discuss the third championship competitor, Danny LaPorte.

Remember Danny LaPorte from earlier? He’s the one that got the Suzuki ride when they weren’t willing to pay Bob Hannah. Just like our first two characters, Danny is going to finish his career with a place in the American motorcycle Hall of Fame, albeit with much less distinction than either Bob or Broc.

Much more likeable as a person than the prickly Bob Hannah or the braggart Broc Glover, Danny LaPorte was simply a kid who grew up spending all day riding his minibike in circles in the backyard, and was so good at this activity that he was never told to stop. Eventually the mini bike turned into a real 125cc, and the backyard turned into local motocross tracks.

Danny got his big break getting swept up in the same big California hiring wave that also brought Bob and Broc to the main stage, only instead of Yamaha, Danny got in at Suzuki. Danny recalls the big push at the time being to defeat Honda. The same is also likely true on the Yamaha end of this tri-way fight. However, the competition is not Honda.

This 1977 championship is going to pit the lone Suzuki rider against both Yamahas, and maybe (given the title) you can see where that’s going, but to understand why the Yamaha riders were put into the position to destroy the purity of this sport forever, we must understand the events of the 1977 125cc national championship.

In 1977, there will be three separate and distinct riding styles going up against each other. First is Bob Hannah, who rides with daring. His style is horrifying to watch, eclectic and unpolished, often letting his feet slip off the pegs, but he never ever lets go of the handlebars (ghosting the bike is a way to turn a bad crash into a more regular one). For his first years as a pro, he’s managed to avoid any big gnarly crashes, but one can come at any time.

Broc Glover, on the other hand, is not Bob Hannah. Even if he could match him on speed, which he can’t, the situation he’s in does not allow him to take such risk as the Hurricane can. Being brought in strictly to be a support rider means crashing in the pursuit of more speed is not acceptable, meaning Broc is going to have to ride well within his means for the whole season, winning only if winning comes easily.

Danny LaPorte is without these restrictions. He can go as hard as he wants, but he doesn’t. Instead, he will spend the whole season playing it safe for points in an effort to win the championship, not necessarily every single race.

What affords Danny the freedom to do this is round one at Hangtown. Yamaha had developed a new and improved cooling system, but was scared out of actually using it by claiming rules that existed at the time. Like claiming rules at horse races, anybody could buy the winning bike after the race at a pre-set (well over market value) price. However, if you’ve just debuted a new cooling system that you don’t want your rivals to see, the perception of the term ‘market value’ changes, and it becomes safer to Yamaha to run inferior versions of their bikes for both Bob and Broc, and this bites them in a big way.

Bob was running away with both races (motocross events are one day, two race shows) until mechanical issues forced him out of each. A seized engine in the first race, and a thrown chain in the second, handed a 1-1 to Suzuki’s Danny LaPorte. This compared to Bob scoring just three points meant Danny was already ahead of his main championship rival, 50 points to three.

Keep in mind this is 1977. The championship is shorter in these days. Only six rounds (12 races). With two of those races already spent creating this massive 47 point hole to close, that means Bob has only ten races to make it up. Considering the gap between first and second is only three points, Bob is already in the position of not controlling his own destiny to a championship, which is what affords Danny the privilege of spending a whole season being able to race safely, taking no risk of crashing, and simply ensuring that he finishes.

This approach is demonstrated in round two at the horribly rough Sandy Oaks. There is no competition for Bob, and he takes an easy 1-1, while Danny plays it safe, coming out of a really treacherous round at a brutal racetrack with a 2-4 and a 37 point lead with eight races to go.

The fifth and sixth races of the season are held at Midland, Michigan. This is not as rough a track as Sandy Oaks, which affords Danny the privilege of going for it a little bit more, but in the end, the points lost here will haunt him in the weeks ahead. Bob still wins the first race easily, and Danny can only come home fourth, losing seven points.

If this playing it safe for points strategy is going to work, these really need to be seconds instead of fourths, but in the second race it’s looking a lot better. Bob gets a really poor start, and spends the race trying to get back to Danny. It’s still only a second place, but with the Yamaha of Broc Glover out front, he feels no need to mess with it. No need to take the risk of Broc putting him on the ground to help out his Yamaha teammate.

Therefore, Danny spends the whole race content to ride in second place, until one of the wildest and most unforeseen (and most forgotten) events in the history of motocross takes place. A spectator somehow finds his way onto the track, and hooks one of Danny’s brake cables in an effort to bring him down.

What the heck?

How could this possibly have happened?

I’ve been to MX events. It’s not that hard to get onto the track if you really want to. That’s not the question I’m asking. The question I’m asking is why would you want to play chicken with the bikes, and if you were going to pick a rider to target with an unfair intervention like this, why did it have to be Danny LaPorte, one of the most likeable MX riders in history?

I don’t know if this was a seriously deluded Bob Hannah fan, or a plant from Yamaha, or anything about this story, and considering it happened in 1977 and it hasn’t come out yet, we will likely never know anything about this story, but what I can tell you is that this fan did get the brake cable hooked, but he did not manage to bring Danny down.

What he did manage to do was skew Danny’s bike to the point it’s almost not rideable, and here comes Bob Hannah. This is an untenable situation, but showing once and for all that he does have the speed to be a national champion (even if he’s refusing to use it), Danny manages to keep Bob behind him until the final lap of the race, where the (broken) brakes catch, and throw him over the handlebars.

This hurts.

In addition to the physical pain of a pretty bad crash, this has gone from a fairly solid day for Danny to a coup for Yamaha. 4-3 for a championship contender is a really bad finish, and Bob’s 1-2 has brought him right back into the championship fight again. In addition, Broc Glover also gets his first win of the season.

You may wonder why I even bothered to introduce Broc Glover at the start if he’s mostly been in the background this entire time. Well, his name is on the title, but more importantly, he’s mostly been doing his job as a support rider up to this point, wedging himself between Bob and Danny every chance he can, and has actually remained quite close to the top two in points himself.

All of a sudden, at the fourth round in Houston, Broc is going to reveal himself as a true championship contender.

This is helped immensely by the fact that Bob does not get any practice before the round. Engine troubles force him out of every practice session. There are no simulators like there are today, so going out to race without any practice means that Bob has no idea which way the track goes. Needless to say, these are not optimal conditions for the man who’s supposed to be Yamaha’s main championship threat.

Going into the first corner of the first race of the day, Bob makes a right turn. The rest of the field makes a left turn, because the track turns left, which Bob would’ve known had he been able to run any practice laps. Needless to say, this causes a crash, and a horrendously bad start. Because Bob Hannah is Bob Hannah, he’s able to work his way all the way back to fifth place, but his Yamaha teammate runs away with the win.

The same thing happens in the second moto. Bob can only finish fifth place. Broc Glover wins, and Danny can only come home with a 4-4, not willing to mix it up with track specialist (something that exists in motocross) Steve Wise. From this point, Yamaha realises that Bob is now too far behind. He’s clearly the superior rider, but their best chance at a championship given the double mechanical failure in round one is Broc Glover, and they begin acting like it.

Bob (still no fan of Broc Glover’s) does not like this at all. He rides the fifth round in St. Joseph, Missouri like a maniac, and takes one of the easiest 1-1’s you will ever see, and this feels like an effort to show Yamaha what a mistake they were making. Would it have been better to let Broc Glover through for the championship? Yes. Of course, but that absolutely was never happening. Danny once again limps to a 4-4. Broc can only manage 3-2.

We go into the final round in San Antonio with Danny LaPorte ten points above Broc Glover, and 17 points above Bob Hannah in the standings. Danny has won only two (the first two) races all season. Broc has only won three, with each of the other five going to Bob. It’s clear to all who the best rider is, but in a points championship consisting of only 12 races, it’s nearly impossible to overcome a double DNF.

Therefore, Yamaha tell Bob that he’s going to have to help Broc in the final round. Bob does not want to do this, so he and Danny (good friends) make a secret agreement that Bob will not help his Yamaha teammate, on the condition that Danny can get in front of Broc, so it isn’t obvious. Danny agrees, and says yes. For the first time since Hangtown, he will actually try to ride his fastest.

To further try to skew the results in their favour, Yamaha pulls all of their riders out of their classes, and tells them that they’re going to ride 125cc, in an effort to get themselves between Broc and Danny to try to bring a championship. Pierre Karsmakers, Rick Burgett, and Mike Bell were all drafted in for this purpose. Karsmakers and Burgett want no part of helping Broc either, and have the stroke not to truly be forced to, so both flake on their duties and spend all of both races riding around in the back. Mike Bell is in a tougher circumstance, but proves not to be fast enough to get in the way anyways, so this attempt at manipulating the results blows up in Yamaha’s face.

Another wrinkle thrown into the works is that Suzuki is bringing their best stuff to the final round. Remember I said before how teams often don’t race their best bikes in America due to claiming rules? That’s out the window for San Antonio. Claims be damned, Suzuki is coming with their best. This sounds like a great thing, but sometimes poor decisions can happen when the big-whigs at these companies make some decisions that they aren’t qualified to make.

Danny does not want this new bike, for the simple reason that he’s never ridden it before. Trying to close out a championship on a bike that he’s never even seen does not sound like a good idea, but he’s overruled. Suzuki forces him onto their full factory RA125, and immediately (within seconds) this proves to be a bad decision.

Danny’s start is brutal, almost certainly due to never having taken a start on this bike before. Immediately, extreme anger runs through his mind, because he told Suzuki executives this was going to happen, and now he’s fallen well back in the pack. The result is that this is one of the most boring MX races I’ve ever seen. Not even worthy of its own paragraph. Danny did not keep up his end of the bargain, so Bob spends the whole race riding in Broc’s tire tracks, making no attempt to pass. Danny can get back up to third but no further, which leaves us going into the final race of the 1977 season with five points between Danny and Broc, and 15 between Danny and Bob.

This 15 point gap means Danny needs only to finish the final race to finish the season ahead of Bob Hannah, meaning he’s accomplished his goal from the beginning of the season to nurse his 47 point lead all the way to the end. However, he (and I, and everybody else, even Bob) got caught off guard, not paying attention to what Broc Glover was doing.

Broc has not ridden great either, but against a rider riding well within his means on purpose, we’ve seen that Broc has been better than Danny for most of the season himself. The five point gap means that if Broc wins and Danny finishes third or worse, Broc will be champion, and with a rider the calibre of Bob Hannah in the race, that’s a realistic scenario. Despite being behind, I would likely bet on Broc to win this championship, based more on Bob’s prowess than his own, but there is one final aspect of this story that may just save Danny’s bacon.

Bob Hannah’s personal dislike for Broc Glover.

Danny gets another poor start, and once again his whole race is spent recovering to third place. This is perfect for Yamaha, but what isn’t perfect is that Bob got off the line ahead of Broc, and he’s gone. Five seconds ahead. Ten seconds ahead. 15 seconds ahead. He’s not slowing down.

Once again, Danny (on his new bike that he did not want, but had forced upon him) has failed on his end of the bargain. In neither race is he able to get ahead of Broc, but this is still in Bob’s hands. Broc has failed his chance to beat his teammate fair and square, meaning the only way Broc (and more importantly, Yamaha) are going to win the championship is if somehow Broc can get in front of Bob Hannah in another way.

There was an understanding before the race that Bob would help, but Bob is not helping.

This can be the downside of having the best MX rider in the world on your team. As Ferrari would later learn with Michael Schumacher in F1, the greats are often very independent-minded, and tend not to go along with things like this, because they have the sway to not have to.

As the laps wind down and keep winding down, and Bob’s lead keeps getting bigger and bigger, it’s clear that he’s not taking the hint. It looks as if Danny’s strategy of shutting it down and riding safely after round one is going to just barely work out for him, and he’s going to win the championship by three points. Nothing would be proven by winning a championship like this, but plaques hang forever.

It’s looking for Broc like it’s going to be close but no cigar for 1977. He’s got plenty of championships ahead of him, so this won’t hurt too badly, but it’d still suck to have to lose a championship to a Suzuki. As for Bob, he’s already proven that he’s the best rider in the world, championship or not, and this win is just going to solidify that point further.

Until.

As all the riders come around for the finish, Broc is ahead of Bob, and in a miracle the tide has turned. Broc has made up 25 seconds in one lap, and has won the 125cc National Championship. Bob coasts home in second place running extremely slowly, and many spectators think he’s either gone down around the back of the track or had some kind of bike problem. Stranger things have been known to happen in this sport.

However, after the race, nobody is celebrating.

Yamaha has just won the championship they’ve put all these resources into. It’s their second in a row, and they can put out into all the magazines (important sources of advertising at the time) that they are the champions. Would they have preferred this championship come as the second in a row from rising star Bob Hannah? Yes, but that doesn’t seem like something that would cause this kind of atmosphere. It’s like a funeral, with only one very happy man in the middle of it.

Yamaha are the national champions. Somebody should be celebrating. The only one who wants to celebrate is Broc Glover, and even he’s holding it in.

The engineers are not celebrating. Bob Hannah is nowhere to be found. For his part, Danny LaPorte looks at Broc’s exuberance and scoffs. He knows what’s just happened here. He at least talks and interacts normally with Broc after the race, but he treats it like a normal race. No handshakes. No abnormal shows of respect. No congratulations for a championship well won.

It all seems so obvious as I’ve written this story, but at the time everybody had an easy enough time passing the weird atmosphere off as fatigue at the end of a long day at the end of a long season. Broc Glover being exuberant and nobody else being exuberant for him is a sight that will become common in the years ahead, so even that is not far enough out of the ordinary to cause a stir, and if it weren’t for a terribly unlucky break, it really could’ve been left at that.

For a few days, it was left at that. However, when the Cycle News and Motocross Action magazines hit newsstands on the Tuesday after the race on Sunday, they don’t lead with anything about Broc Glover. They lead with this.

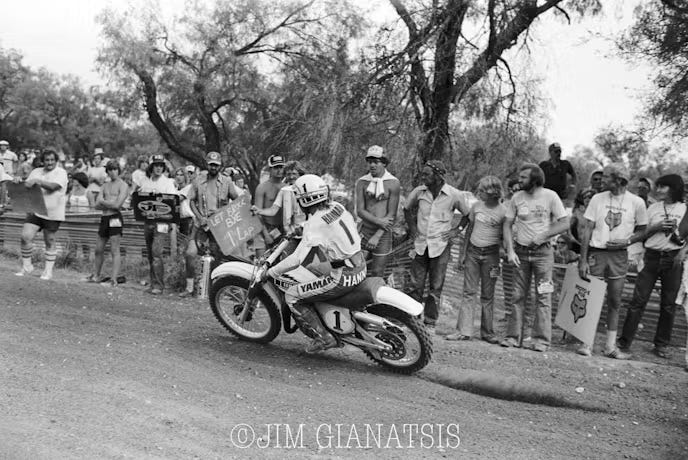

The writing is small in the Jim ‘the Greek’ Gianatsis photograph, but you can see Bob Hannah reading it, and if you zoom in you can see it.

Let Brock Bye.

Three words, two spelling mistakes, and the death of the innocence of American motocross.

Bob Hannah had not gone down around the back of the track. He had not had a mechanical problem. Yamaha had seen that Bob was not going to take the hint, and unless they gave him an order, the team could not reprimand him for refusing to obey the order, so on the final lap (where it would be the very most obvious) Yamaha were backed into the corner of having to tell Bob Hannah (the best rider in the world) to somehow find a way to convincingly lose 25 seconds and let his teammate past, and to do it immediately, because the other writing on that pit board tells Bob that there is only one lap to go.

There is no convincing way to lose 25 seconds in one lap. Not if you’re Bob Hannah, but being the smart rider he is, Bob goes all the way around to the back end of the track (where there are no spectators) and stops. He waits for Broc to go by, and then he goes again. Perhaps if anybody had seen, he could claim that the bike had quit (something that happens from time to time), which was likely the plan, and it could’ve worked if not for pesky journalists being really good at their jobs.

Jim Gianatsis (of Cycle News) and Jody Weisel (of Motocross Action) were finished for the day. The race was over, they thought, and they had no reason not to think that with Bob being ahead by 25 seconds. There were no more pictures to take. They were both just standing and chatting with each other at the mechanics’ area, likely getting ready to snap pictures of Bob taking the chequered flag in one lap’s time.

However, a good photographer always has their camera ready, and both men noticed something odd. Why was the man in front by 25 seconds being shown a pit board? What possible further instructions could the team have to give? Both reacted quickly, and took what would become the most famous picture in the history of American motocross. There are two variations of the above photograph, taken by two different people, but you’d be forgiven for not knowing (I didn’t know before writing this), because both photographers were standing right beside each other, and took the exact same photo.

The photo that would be the death of the popularity of American motocross.

Jim did not know what he’d just shot, and didn’t know that he was about to blow up the world until he developed his negatives. Jody knew what he’d seen though, and everybody else did too. Both Broc Glover personally and team Yamaha were all over him to destroy the negative (not knowing that the Greek had shot the same photograph), but Jody stood strong, and printed it.

Along with the photograph, other elements of this story began being revealed. Recall that after the race, Bob Hannah had disappeared, and nobody could find him. In the aftermath of the photograph’s release, Bob saw no reason to hide the fact that he’d ridden into the forest and cried, waiting long enough out there to not have to face any media when he came back.

Bob was given a team order to screw his good buddy Danny LaPorte out of the championship, and hand it to the hated golden boy. He obeyed that order, but he hated doing it, and he hated himself for doing it. He went to Yamaha HQ and demanded that he be paid Broc’s championship bonus (he got it), but still never forgave himself or Yamaha for allowing this to happen. He knew what this meant to the sport.

Bob never got over his personal regret at this action, even as he finished a career that featured 70 race wins and 13 championships. It would be a root factor in his decision to leave Yamaha in 1981, demonstrating that even after four years he hadn’t forgotten. He’ll never forget.

Bob Hannah is still alive (at the age of 68 years old), but I bet he’ll take his regrets at his decision to take the championship from his buddy and give it to the golden boy to the grave with him. Below is an outstanding picture of a Yamaha engineer (in literal terms) holding the pit board over Bob’s head (far left) as he sits next to his friend Danny.

Even more important than the effect it had on Bob Hannah is the effect that this one picture had on the sport of motocross as a whole.

Team orders are a thing in international racing. They’re more or less accepted as part of doing business, but this is the one aspect of the sport that the Europeans did not bring over with them. Americans do not like team orders, and as of 1977, they were barred by the AMA. As a result, once the photo is released, people fully expect penalties for all of Broc Glover, Bob Hannah, and team Yamaha, and a championship for Danny LaPorte after all.

However, the AMA bizarrely finds in their investigation that they have no reason to suspect foul play on the part of Yamaha, and allows the championship to stand. Even more bizarrely, they say that a key element in this finding was their complete inability to contact Yamaha team manager Kenny Clark.

That’s like saying the key reason that robbing a bank is legal is that you couldn’t find the bank robber. Of course you couldn’t find Kenny Clark. That’s no reason to call off the investigation.

What about Pierre Karsmakers, Rick Burgett, and Mike Bell? You couldn’t have found them and asked what purpose they were entered into the race for? What about Bob Hannah? You know, the most famous MX rider alive? You couldn’t find him? You and I both know he would’ve fessed up to the foul play.

Even if somehow the AMA was saddled with the complete inability to have any contact with any of these people, we know for a fact that they were delivered a copy of Motocross Action, with the big ‘Let Brock Bye’ photo on the front, because the editor went on record, ensuring that the AMA had seen the photo.

Oddly enough, team Suzuki seemed to be okay with all of this. It was the fans that’d launched the initial protest into the results (something that is almost never done, but technically can be done in MX racing). Only extremely reluctantly, once it became clear that not protesting was creating more backlash than protesting, did Suzuki launch their own protest of the results.

At first the AMA feigned ignorance, which is when the editor of Motocross Action had to go on record to make it perfectly clear that the AMA had at least seen the photo, as I described above. After the ignorance ploy failed, the Association simply had to say that they did not find it to be a rules violation, with their defence basically coming down to admitting that they’re too stupid to read their own rulebook.

This is how you kill a sport.

On August 14, 1977 (the day of the final round in San Antonio), motocross was viewed as a fierce duel. Man against man, with respect shared all around. Sportsmanship was still real in American racing at the time. Notice that this championship (even amongst everybody hating Broc Glover) had none of the knock down, drag out, contact-filled battles that’d become so prevalent by the time Mike Brown faced Grant Langston in this same 125cc class 24 years afterwards. These were sporting events conducted amongst people who respected each other, and that’s how the public looked at it.

When the AMA came out with their ruling, and it’d become clear that they’d bent over backwards to help Yamaha, and that Suzuki didn’t even seem to mind, the entire perception of the sport changed.

Instead of gladiators fighting intense but respectful wars against each other, the manufacturers can now just alter the results as they see fit. They can alter the rules to make it okay to do so, and the governing body is either hopelessly corrupt or hopelessly inept depending on who you ask, but it really doesn’t matter which description is correct because the result in both cases is the same:

These are not duels between brave young men, these are corporate shell games between the big manufacturers.

It only takes one incident like this for the public to lose trust in a sport, and once it’s gone it takes decades to come back, which is why I called Jim and Jody snapping the photo an unlucky break. These two are fantastic at the their jobs, and this had to be shared with the world, but if only the two had been too engrossed in their conversation to see that pit board. Things could’ve turned out a lot differently for the sport of motocross.

It’s not that the public didn’t know things like this were happening. They did, but disbelief can be suspended until encountered with overwhelming evidence to the contrary. This reminds me of when the WWF began admitting pro wrestling was not a sport, starting in 1989. As soon as they did this, they’d killed the golden goose, because despite how visually obvious anything may be, until confronted with an admission, it is possible to suspend disbelief.

Pro wrestling since 1989 has never been as popular as it was before 1989, and the same is true for motocross with this incident in 1977.

People can tell pro wrestling is not true competition. People can tell that the manufacturers are the real people running the sport of motocross, but until presented with an irrefutable counterexample, they will close their eyes and pretend that they don’t see it, because people want purity in their sports. Motocross destroyed the purity of itself, just like pro wrestling did in 1989, just like NASCAR did in 2004, and just like the NHL and MLB did with their players’ strikes in the 1990s.

In 1977, the trust of the fans was violated. Once that happens, they do not forgive. It’s been almost 50 years since that day in San Antonio, and American motocross has never recovered, and American motocross never will recover. Too much damage was done (by just one photograph) for the American public to ever be able to forgive.

The sad part is that this, like every other loss of innocence in the sports world, was so easily avoidable. As it turns out, Yamaha got so much hate for winning this championship this way that it would’ve been better advertising not to win the championship. Even if they felt the need to win at all costs like this, couldn’t they have given the order at the halfway mark to allow Bob to lose 2 seconds per lap and not make it so visually obvious?

They didn’t do that, and because they didn’t do that, they had killed the golden goose. They’d violated the fans’ trust. It’s 47 years later, and the sport of MX racing still hasn’t gotten that trust back.

That’s why nobody cares about motocross.

It’s a real shame too, because this is a great sport, but fans don’t like when their sports are interlaced with the real world, and just like the real world, the big businesses just couldn’t help but put their fingers in the motocross pie, and it ruined it for everybody.

Thanks so much for reading.

Great story here. It's remarkable how one photo can have such lasting consequences for an entire sport. I relate to the pro wrestling comparison - I was never able to watch it the same way after learning it was predetermined. Oddly enough though, even the NBA's Tim Donaghy scandal didn't hit quite as hard - maybe because there wasn't such clear evidence of manipulation like there was here. Something about seeing that pit board makes it impossible to look away.

This is an incredible story and incredible narrative. But as a pro wrestling fan, I would challenge the use of "fake". Pro wrestling is predetermined. But I've seen more than one broken neck and 2 broken tibias in pro wrestling matches. And honestly, as someone who's worked in pro wrestling, mma and boxing. Pro wrestling is at least honest about being predetermined. Fake implies that there's no risk.