Separating Skill From Results: An Analysis of QB Skill in the NFL

Breaking down QB play into individual skills, and using those skills to rank every post-merger NFL QB.

Welcome back to my Sports Passion Project everybody, where in the words of my good friend

, I am obsessed with ranking everybody against everybody else.This article is the culmination of a months (and perhaps years) long quest of mine, to find a results-agnostic QB performance indicator that I can have significant trust in, and also serves as the final chapter to the statistical story arc that this publication has been on for a while now. Hopefully, this article can be the end of my ruthless quest to find statistical truths about the NFL, and finally we can go back to telling some stories around here, but for now, let’s talk about QB skill in the NFL.

I’ll begin by talking about some things that are not skills.

Throwing touchdown passes is not a skill, because the opportunity to throw a touchdown is much too circumstantial. In a close to home example, the Trent Green series focuses heavily on this point, as with Priest Holmes on the team, Trent simply accounts for far fewer of his team’s touchdowns than a QB of Trent’s calibre would have in a different situation, because comparable QBs didn’t have the best RB peak of all time on their roster (I did just say that), and Trent Green did. Playing on a different team, Trent could’ve had as many as ten touchdowns more per season in his prime, based on factors that have nothing to do with him. Touchdowns are a results measure, not a skills measure.

Better results measures are not immune to the same problem. Take for example EPA/Play. This is my favourite results measure, because it takes into account everything that happens in a game, but this also can prove to be its biggest hinderance when trying to interpret it as a skills measure.

Think about a QB facing first and ten from his own ten yard line. On this first down, he completes a simple drag route. From here, the paths diverge. If that QB is playing with generally good receivers, there’s a solid likelihood that the receiver will turn the corner for a first down, and a positive EPA contribution goes on the QB’s box score. If it’s a more mediocre receiver, the most likely outcome is a catch and immediate tackle, for a second and five situation, which is basically a zero EPA contribution for the QB. It didn’t make the team more likely to score, but it didn’t hurt the team either.

The difference in these two plays was the receiver. Not the QB, and that oftentimes can be the crux of the disconnect when discussing QB skills vs QB results. Things like having a lot of passing yards, a lot of touchdown passes, and a lot of EPA/Play are results of being a very skilled player, but are not individually indicative of any particular skill.

It’s natural for the correlation between skill and result to be extremely strong. If it isn’t strong, that’s generally an indicator that you’ve selected the wrong skill for analysis. For instance, in ice hockey, having a hard shot seems like a useful skill in a vacuum, but when you look at the correlation between a player’s results and how hard they can shoot the puck (particularly as a defenceman), it’s just not there. This means that shooting the puck hard is a skill (as it’s not dependent on outcome), but it’s not a very valued skill. This lays bare the importance of selecting the correct skills when trying to build a measure of how good a player is.

There exist skills of this nature in the QB world too. For instance, the ability to hold the ball for a long time before throwing it is a skill. When you look at the time to throw rankings in 2024, the man that held the ball the very longest (skill) was Lamar Jackson, who also happened to rank second in EPA/Play (result). The QB that on average held the ball the second longest (skill) was Jalen Hurts, who won the Super Bowl (result). On the surface, this seems like a very healthy positive correlation. Hold the ball longer, and get better results out of it, but when you continue looking, Jared Goff threw the ball 18th quickest, Joe Burrow threw it 13th quickest, and all of Baker Mayfield, Jayden Daniels, and Tua Tagovailoa were in both the ten quickest throwers of the football, and the top ten in EPA/Play.

The correlation between the skill of getting the ball out quickly and the results of these plays is extremely light. Therefore, this is a skill, but it is not a particularly valuable skill. You can be a great QB without it. That is not the kind of skill I’m searching for here. The skills I look to include in my model are indispensable, the kind you can’t be a great QB if you don’t have.

For an NFL QB, in my opinion, there are just two skills of this variety. Two skills that you can’t make a living if you don’t have. I’ll get into the statistical nitty gritty later, but for now, I’ll state them in plain English. First, you must be able to get the ball out of your hands. You cannot be tackled in the backfield for a sack. Then, given that the ball is out of your hands, you must be able to make the throw.

I listed these two skills in that order on purpose. That is the sequence of the play for the QB (first avoid getting sacked, and then make the throw), and because of that sequencing, it is also the order of importance. A lot is made about the arm of a QB, but if the ball never gets in the air, that golden arm does not matter. It never gets the chance to matter, unless you can manage to avoid being tackled by the pass rushers first. The ability to actually throw will come into play on most QB touches, but the ability to avoid a sack matters on every single drop back.

You may notice that I’ve intentionally left the definitions of these skills very vague, and that’s also intentional, because in each case, there is more than one way to get the job done.

Let’s begin with sack avoidance. There are many different ways to do it. All are equally valid, as far as I’m concerned. The first and most obvious way to avoid being sacked is what I call the Tom Brady method. Constantly rank near the quickest in the league in time to throw, and simply throw the ball before the defenders can ever get near you. A modern example of this phenomenon would be Tua Tagovailoa.

The Tom Brady method is the way that most players who are not very good try to go about their sack avoidance, but for good players, there are ways to avoid sacks while not throwing the ball so quickly. The most common is what I would call the Peyton Manning method, which is to be a wizard with your footwork. You don’t have to be the most athletic player in the world to pull this off, but your feet must always be moving in the pocket, constantly stepping in the right direction to keep yourself so close, yet so far away from being sacked. In the modern game, Derek Carr is a savant at this exact thing.

These two methods of sack avoidance account for about 98 percent (or better) of all QBs who have ever played, but there is also a third way to avoid being sacked, for which the best historical example is also the best modern example. It’s the Lamar Jackson method, which generally entails being an athletic freak that defenders just cannot keep up with, but also having razor sharp eyes for rushing lanes, such that failed scramble attempts do not also turn into negative plays.

I have described these methods as if they’re binary, but generally, players mix these strategies together. Look at Josh Allen’s sack avoidance style. I would say it’s roughly 75% the Peyton Manning method, of always having his feet under him, moving in the right direction to avoid the rushers, plus 25% of the Lamar Jackson method, being the athletic marvel that Josh Allen is.

The point of all this is that there are many ways for a QB to ensure that he does not get tackled in the backfield. It does not matter to me which method he uses for the purpose of this analysis, because the focus is in avoiding the negative play, not in how the negative play is avoided. Derek Carr is an exclusive connoisseur of the Peyton Manning method, and he was the NFL’s best at avoiding sacks in 2024, but Cooper Rush was all about the Tom Brady quick throws method, and he finished fifth in sack rate.

Both players are fantastic at the fundamental skill of ensuring that they can at least throw the ball, and that’s what we need to know. The Lamar Jackson method of being an athletic freak to avoid sacks is often what’s shown on the highlights, and often leads to overrating the people who use it, but it’s important to keep in your mind that we’re not grading the method. We’re grading the ability to ensure that as many drop backs as possible reach the stage where they can end in a pass attempt. I don’t care exactly how it’s done.

The statistic I will use as a proxy measurement for this skill is simple. It’s just sack rate. For the purposes of the model, I will use pro football reference’s sk%+ statistic, which normalises a player’s sack rate to the average for his league and time. The NFL average sack rate has not changed an extreme amount throughout history, but it is about 1.2 percent better than it was when the NFL and AFL merged in 1970 as the league average QB has improved in general, so normalisation is important.

One thing I must get out of the way, before it’s brought up in the comments, is that sack rate can sometimes be a function of a QB’s offensive line, but in a game where one must rely on his teammates as much as a QB must in football, his sack rate is actually the thing he has the very most individual control over. A QB accounts for about 45 percent of his own sack rate every year. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but once I tell you that the previous year’s TD pass total can explain about 20 percent of next year’s TD pass total leaguewide, you will begin to understand just how much control that is, in a game where (even at the most important position) individual players possess very little independent control. 45 percent leaves only 55 percent for other things (new scheme, differing offensive line quality, etc.) to affect the outcome in terms of sacks every year. This makes very clear that the very most important individual factor to a QB’s sack rate is the play of the QB himself, something that can’t be said about most results measures.

So, we’ve discussed our first necessary skill. A QB must stay alive long enough in the pocket to be able to actually throw the ball. It will be measured by pro football reference’s sk%+, but what happens once a QB actually gets the ball out of his hands?

That’s where we get into our second (intentionally vague) skill. The ability to make the throws. Making a throw is actually a very similar story to avoiding a sack. There’s more than one way to do it, and as long as a player is able to get it done, I don’t necessarily care which method he uses.

There is what can be called the Brett Favre method, where a player routinely attempts immensely difficult passes, but uses his God given arm talent to fit the ball where it has no business fitting. The best modern example of this is still Josh Allen, who even as his throws have been getting easier and easier over the years, still attempts the most difficult throws amongst the crop of great QBs.

There’s also what I would call the Patrick Mahomes method, which I would generally describe as being a game manager most of the time, but never missing the big play when it comes open. Patrick is the ultimate (modern or historical) example of this play style, but I must also say that Derek Carr is fantastic at this.

Contrary to what most believe, it is also possible to be a great thrower of the football while also playing in a game manager style all the time. This generally entails short (but not always easy) throws, normally (but not always) used by players with poor WR rooms. I would describe Tom Brady as the ultimate historical example of a game manager who made it work, and for examples in the modern game, both Tua Tagovailoa and Kyler Murray fit the bill, in terms of throw selection.

Everybody who does not fit into any of these three unique categories ends up in a fourth method, where basically all passes are between four and eight air yards long, with some big plays interspersed in the middle, but also some big plays missed. This is basically the mushy middle in terms of throw selection, but note that you can be great this way. I would describe guys like Joe Burrow, Jayden Daniels, and Jalen Hurts as mushy middle throwers. It’s because of their immense abilities to make these mushy middle passes that these guys are great players.

Notice that I did not mention such a nebulous concept as ‘arm strength’ anywhere, in any of these categories. Arm strength is like a hard shot in ice hockey. It’s nice to have, but it’s a skill that makes someone greater. It’s not a skill that makes someone great. If you’re in a position as a QB such that your arm strength matters, and is a topic of discussion, you’re already a great player. Sure, a strong arm would make you greater, but it did not hinder you from being great.

For a historical example of this exact phenomenon, I always love to use Chad Pennington. Did you know that Chad often ranked among the very best in the NFL on passes longer than 20 air yards? Most people do not remember that about his career. There is all kinds of talk on the internet about Chad’s poor arm strength, and, because I don’t care about arm strength, I’ll admit that it’s true. He had perhaps the weakest arm for any MVP level QB ever, especially after the injuries.

People loved to talk about ‘noodle arm’ Chad, but what they always dislike when I bring up that it simply didn’t hurt him that badly. On passes of 20 air yards and longer, Chad was not just fine despite his weak arm, he was very good despite his weak arm, and it’s another example of just what I was saying above. We’re not grading the method.

Were Chad’s moon balls (not a Russell Wilson invention, no matter how much the media tells you) on 25 yard passes ugly? Of course they were. It was hard to believe that this guy could even be an NFL QB when you were watching a ball go up the way it often did out of Chad’s hands, but the fact of the matter is that they came down for 25 yard completions more often than they didn’t, and that’s all we care about here.

For the measure of a QB’s ability to complete a throw, regardless of its depth, I will be using NFLFastR’s version of the CPOE (Completion Percentage Over Expected) statistic ever since it began being measured in 2006, and before then, I will be using my own historical CPOE model, explained here, including historical leaderboards, which goes all the way back to the NFL-AFL merger in 1970.

CPOE requires assigning an expected completion percentage to every throw, and aggregates all throws at the end of the season into a year long expected completion percentage for every QB. Subtracting this expected completion percentage from a player’s actual completion percentage gives Completion Percentage Over Expected. If it’s negative, a player completes fewer passes (makes fewer throws) than the league average QB can. If it’s positive, a player makes more throws than the league average QB.

Short of sack rate, CPOE is the best QB skill statistic you’re going to be able to get. It is much less in the QB’s hands than sack rate is, as a QB can explain only about 33 percent of the variation in his own CPOE from year to year, but once again, this is a staggering amount of control for an individual to have over his own numbers in the NFL.

Adding CPOE gives us now two measures of QB skill, that hold no matter the results of their plays. On their own, these two statistics are a very solid measure of the individual skill of every QB in the NFL. One measures their ability to ensure that they have the opportunity to throw. The other measures their accuracy on the ensuing throw, which also bakes in the skill of attempting the right throw in the flow of the offence, but when I first posited this model a couple months ago, my friend

brought to my mind a necessary revision.There are three outcomes that can happen on any QB drop back.

First is a sack. These can happen at any time. There are also pass attempts, which can happen if a sack does not, but in between these two events in the timeline also lies the possibility of a rushing attempt. At any given time, assuming a sack has not happened, a QB can choose to either rush or throw, but cannot run once a throw has happened, cannot throw once a run has happened, and cannot do either once a sack has happened.

This is a three-way interaction. It is not a two-way interaction, so modelling it with just two variables is not correct. There must also be a measurement of a QB’s rushing performance. Considering the purpose of including rushing totals is to model the ability for a QB to make a choice, at first I was going to just use total carries as my rushing variable of choice, but that idea got caught up when the concept of the QB sneak began showing its ugly face.

There has been a lot of talk about the QB sneak recently, now that teams have actually begun finding ways to be good at it, but the tale is actually as old as time. QB sneak attempts are a function of the quality of the offence that a QB is a part of. Not necessarily a function of the QB himself. Therefore, the idea of modelling carries as if they strictly were a QB choice would introduce a fatal flaw into my methodology.

Instead, I’ve decided to use rushing yards per touch as my rushing measure of choice. This is not rushing yards per rushing attempt. This is rushing yards per total touch. This inherently models the fact that rushing for a QB is a choice. To a degree, the QB has a choice over how many of his total touches are devoted to passing, and how many are devoted to rushing. A QB can have a high yards per carry total, but very rarely carry the ball. Is this indicative of a big rushing contribution? I don’t think so.

At the same time, a QB with a comparatively low yards per carry total, but one who does choose to rush a lot, can still accrue upwards of 500 yards rushing, should he choose to do so. This is a large contribution, and if it comes at the expense of the other aspects of his game, that will be captured, because this model also includes measures of how well a QB does when throwing the ball, and how good he is in the pocket.

So, with one alteration, we now have the three QB skills, and their associated measurements, with which we are going to build a model of QB skill. How exactly should we go about this?

The first step is always to check for correlations, and the standard results apply. There are significant correlations between all of them. There is a significant negative correlation between rushing yards and both sack rate and CPOE, meaning that QBs who choose to rush more often, and rush for a lot more yards, often do so at the expense of the other aspects of their game. However, the correlation between CPOE and sack rate is significantly positive. It is extremely small, so likely does not necessarily need to be accounted for, but I will account for it anyway.

The simplest possible way to do this in a statistical sense is via the use of interaction terms. In English, they are a way to account for the fact that a lot of rushing yards is a great thing to have, but they also tend to be a cause for a player to have a very high sack rate. Therefore, 1.2 rushing yards per total touch (an extremely high value) with a sk%+ of 90 will result in a fundamentally different rushing contribution than 1.2 rushing yards per touch on a 110 sk%+. The former would generally imply somebody who puts their head down to try to run, but often ends up running directly into the pass rushers. This person should likely run the ball a bit less, but the latter would imply somebody who runs because they see a lane, and are very good at seeing lanes. This person should perhaps think about running more.

The same goes for all the other cross correlations. A runner who can throw gets a different score (even in the rushing category) than one who can’t, and since the ability to avoid sacks is (very lightly) aided by being very good at throwing the football, sack avoidance is given a very slight boost when being done by somebody who cannot throw accurately.

These all work in reverse as well. People who can avoid sacks, but not run, get a fundamentally different score than those who avoid sacks but do run, even in the sack avoidance area, and etcetera.

Okay. Now that I’ve finally got everything explained, it’s finally time to show some results.

In order to do this, and put things in a perspective that we can all understand, I’ve fitted my QB skill measure to an EPA/Play scale. This gives birth to a very unruly Expected Expected Points Added per Play, or xEPA/Play, statistic. The way to interpret this is that if every QB in the league had the exact same quality of receiver group, exact same quality of offensive line, exact same quality of offensive coaching, exact same game situations, and exact same luck (turnover luck, weather condition luck, etc.), these would be the EPA/Play rankings in any particular post-merger NFL season.

This xEPA/Play statistic tracks real EPA/Play at an R-Square of approximately 70 percent, which we can loosely interpret as the quality of a QB’s play accounting for roughly 70 percent of his results in any given season, leaving 30 percent up to be decided by things beyond a QB’s control (receiver quality, turnover luck, etc.). To me, this passes the eye test. It tracks with what I’ve seen. For an unrelated exercise, I once calculated that the average volatility in Aaron Rodgers’ EPA/Play on a season to season basis was about a third of his career EPA/Play. This would align very nicely with the idea of him being in control of 70 percent of his own results.

Some people would think this is way too much control to assign to the QB. Others would think that it is much too little, but for the remainder of this exercise, we’re going to proceed with the assumption that a QB is in control of roughly 70 percent of his EPA/Play outcome.

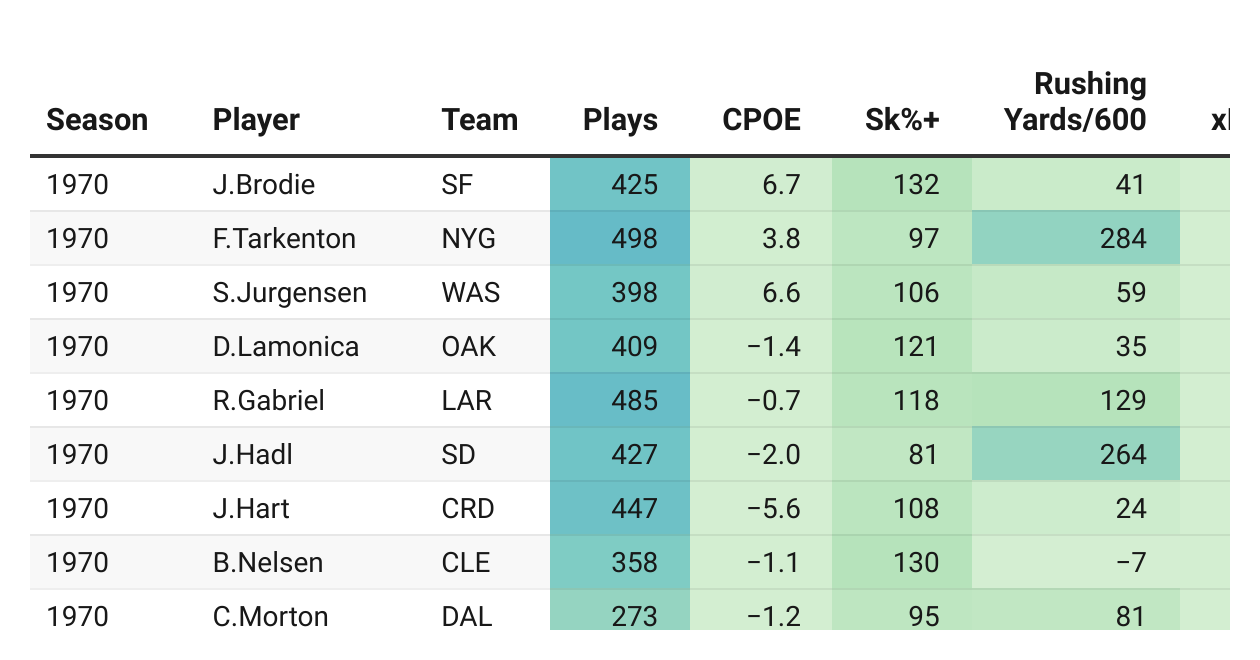

The ground rules for navigating the beneath table are the same as they were for the CPOE table last month. The default sort is my QB tier list for every season before 1999 (which are strictly results based), before switching to the EPA/Play rankings from 1999 onwards, as a means of testing the correlation between QB skill and QB results. If you want to sort by something else, simply click on the corresponding label.

If you want to look at one player’s career, season by season, type the first letter of his first name [dot] his entire last name into the search box, as in ‘P.Manning.’ If you want to look at the QB skill rankings within one season, type that season into the search box. I would highly recommend ‘1994,’ where in the top five of the QB skill rankings, you’ll see on the top of the list the four QB icons of the 1990s, along with everybody’s second favourite Sports Passion Project passion project, Jim Everett. ‘2000’ is also a good one, where everybody is sure to simply accept the two names immediately above Peyton Manning, and oh my God. Is that Tim Couch?

(P.S. I’ve scaled rushing yards to be per 600 touches for this table, to create season ending numbers more interpretable to fans used to looking at end of season statistics.)

This table is also an example of how multiple things can be true at once. For a perfect example of this, we move to everybody’s favourite Sports Passion Project passion project, Trent Green. Your homework assignment is to type ‘T.Green’ into the search box.

The narrative surrounding Trent Green is that he was carried by his weapons for his career in Kansas City, but a chart like this shows that to be both factual and less than factual at once. In 2002, Trent’s 0.148 xEPA/Play turned into 0.211 real EPA/Play, which is a shockingly large difference, indicative of a strong carry by the KC offence. However, in both 2003 and 2004, Trent’s individual skill caught up to his results, and for the rest of his career, his skill matched his results almost exactly.

This is the kind of analysis you can do with a chart (and metric) like this. Think of anybody you want whose perception is that they’re being carried by their weapons, and this table will prove that either correct or incorrect. For instance, I think the two worst culprits in the modern NFL of getting great results despite lacking the requisite individual skill are Matthew Stafford and CJ Stroud, and xEPA/Play agrees with me on both counts.

CJ Stroud’s 0.058 xEPA/Play in 2023 is very far behind the 0.124 EPA/Play he actually posted, indicating a strong carry job out of the Houston offence, and his -0.006 xEPA/Play is almost exactly his -0.007 actual EPA/Play in 2024, indicating that it should not have been any better than it was. For Matthew Stafford, there has been one season in his entire career where he has failed to benefit from his offensive environment, and that’s his horrendous -0.019 xEPA/Play turning into an even worse -0.061 actual EPA/Play on the awful 2022 Los Angeles Rams. Every other season of his entire career, his results have been better than his skills have deserved, largely buoyed by having the benefit of Calvin Johnson for most of his career, plus the best (production-wise) WR season of all time in 2021 out of Cooper Kupp, plus all the other benefits that being in a McVay offence comes with.

However, I don’t like to just be negative all the time, so there are some people I would like to exonerate from their unearned reputations of being products of their offensive environments. Kurt Warner in St Louis seems like a good example. His actual results do still come in above his xEPA/Play, but the Greatest Show on Turf does feature two of the best 30 xEPA/Play seasons of all time out of Kurt. That just goes to show that even if a QB is the best in the world, he can still be carried to results better than he deserves by a ridiculous receiver group, and extraordinary offensive environment in general. This does not disqualify him from being the best QB in the world. Other examples of the same phenomenon include 1984 Dan Marino, 2004 Peyton Manning, 2007 Tom Brady, 2011 Aaron Rodgers, etc..

To use Peyton as the example, his 2004 is the sixth best xEPA/Play season ever, but nevertheless, his 0.443 EPA/Play is mountains above his 0.330 xEPA/Play, because he got carried to that level by having three of the NFL’s top twelve receivers in Marvin Harrison, Reggie Wayne, and Brandon Stokley. The same goes for Tom’s 0.302 xEPA/Play in 2007 being turned into 0.422 actual EPA/Play by two of the league’s best five receivers in Wes Welker and Randy Moss.

That’s what makes two all-time great QB seasons into the best results-based QB seasons ever. It takes both skill and luck.

That’s a lot of the high points that I think the general public would like to know. From there, we can move onto some Sports Passion Project specials. For instance, 1988 Steve Pelluer (a season becoming well known on this publication) sees him rank seventh in xEPA/Play with 0.163, before being kicked to the curb in favour of Troy Aikman and never being given a real chance again. This is still a horrifying decision on the part of the league.

Another thing I wanted to do is look over some of the more famous one-offs of all time, and check whether they were functions of the offensive environment, or if they were truly one season where a player got it all together. The simple answer is that it goes both ways. For instance, Case Keenum in 2017 is a true skill-based one-off, generating 0.193 xEPA/Play in his magical run, and never getting above 0.042 in a season again. Meanwhile, somebody like Cam Newton in 2015 was likely always a mirage, as you can’t even pick out 2015 on his career rundown in the table. His xEPA figures were not out of line with the rest of his career, but his actual results were, likely a function of the offensive environment he was in.

I can talk for hours about all the fun things I can do with this table, but I think it’s time we move onto the main event, don’t you? This is the question that everybody reading this article has surely been wondering to themselves. It’s the question that this whole analysis was formulated in an attempt to answer.

Who is the most skilled QB of all time?

The following is a table featuring all 214 NFL QBs since the NFL-AFL merger to reach at least 1000 career touches, ranked by their career xEPA/Play. You can interpret it as a best QBs of all time list, but do keep in mind that it has the same follies as any career rate statistic. Players who have not had their falloff yet (i.e. Patrick Mahomes and Josh Allen, both top 15) are helped a lot. Players whose careers ended due to injury, never getting a chance to fall off (i.e. Chad Pennington, Roger Staubach) are helped a lot. Players who did not play as unready rookies (i.e. Steve Young, Patrick Mahomes again, and all the pre-merger holdovers) are helped a lot.

Keep in mind that wherever you see an active player, this is not their final ranking. If they’re currently in their prime, it’s almost assured that they will fall from here, once their prime ends, unless their career ends in the middle of their prime, in the way Chad Pennington’s or Tony Romo’s did.

Take this table for what it is. It’s a career rate stat, so it comes with all the pitfalls that career rate stats come with, but this is every post-merger NFL QB, ranked by their level of skill, showcased over their entire career:

Okay, so it’s a bit of an anticlimax to say the best results-based QB ever is also the best skills-based QB ever.

It was always going to be Peyton Manning, wasn’t it?

Peyton’s primary skill is that he was the second best sack avoider ever. By career sk%+, he’s behind only Dan Marino, and Dan Marino is not in the top ten in career CPOE, like Peyton Manning is. There’s no rushing contribution at all from Peyton at any time after the year 2002, but with that combination of skills, being the second best of all time at ensuring the ball gets into the air, and amongst the ten best of all time once it’s in the air, why would you ever run with the football? That wouldn’t make any sense, and Peyton did not take long to come to that realisation himself.

He spent a whole career strictly using his arm to get his damage done, and in terms of individual skill, he did it better than anybody else. This is not surprising. Once again, in terms of individual results, nobody can best Peyton Manning (on a rate basis) either, so it’s not surprising that he’d end up on top of this list, but what did surprise me is the man he had to fight to the death in order to defeat.

Steve Young’s career sk%+ is 94. This model is hardwired to believe that sack avoidance is the most important skill in the game for a QB to have. In other words, the formula is designed to hate him, but Steve Young just doesn’t care. Through the sheer strength of being number one all-time in career CPOE, plus also being the very best retired rushing QB, he almost overcame a formula (and sport) specifically designed to hate this style of play in order to be proclaimed the best QB of all time, falling short by just one thousandth of an xEPA/Play. Over a 4731 play career, that’s still (in literal terms) one play short.

There are other interesting names on this leaderboard. Like I said before, with the active players, their ranking is sure to fall once all is said and done, so pay little heed for now to names like Jalen Hurts, Brock Purdy, and Jordan Love in the top 25 QBs of all time. Ignoring all these guys, and ignoring the pre-merger holdovers of John Brodie and Norm Snead, each of whom barely got to 1000 post-merger touches, there is still one name that sticks out like a sore thumb in the top 25.

I need you to take note that the top 25 most skilled QBs of all time list does not feature Tom Brady. Nor does it feature Aaron Rodgers. It does not take much scrolling to find them. They are both right at the top of page two, but I invoke their names to get across to you the fact that this list is extremely exclusive. It’s not an easy list to get onto.

With that being said, what the heck is Chad Pennington doing here?

To begin, it must be said that he is advantaged by the formulation. His career ended before his prime did, due to injury, with Chad completing his last full season at the age of 32. There was no falloff for him, which always helps when dealing with career-long rate statistics, but you do not get to 0.174 career xEPA/Play just by not falling off.

Chad Pennington’s 2002 in particular is uniquely great. I know I talk about 2002 Pennington a lot, but it deserves to be talked about even more. Chad is one of just 11 people to ever have a season of a CPOE as good as 7.5, and a sk%+ as good as 109. Chad and Norm Snead are the only two people to ever put up a season this good, and fail to make the Hall of Fame. The other nine are Ken Stabler, Kurt Warner, Fran Tarkenton, Joe Montana, Philip Rivers, Tom Brady, Drew Brees, Steve Young, and Peyton Manning, all of whom are either gone or going into the Hall of Fame.

One great season does not make a Hall of Fame player, or a top 15 most skilled QB of all time, but Chad posted a 7.4 CPOE in 2007 also, making him one of just 13 players to have multiple seasons of seven CPOE or better. The other 12 are Ken Stabler, Kurt Warner, Steve Young, Russell Wilson, Roger Staubach, Peyton Manning, Ken Anderson, Fran Tarkenton, Drew Brees, Bob Griese, and Aaron Rodgers. All of these guys are Hall of Fame calibre players, and Chad Pennington is their company on this list.

Add onto these two seasons Chad’s 5 CPOE, 108 sk%+, 0.195 xEPA/Play 2008, and his 3.4 CPOE, 114 sk%+, 0.187 xEPA/Play 2004, and we’ve accounted for three quarters of Chad’s career plays already. As far as I’m concerned, this is a Hall of Fame calibre talent, even after his shoulder injuries, that did not make the Hall of Fame for one reason.

Only once in his entire career did Chad’s actual results live up to his xEPA/Play.

That one time is actually his 0.259 xEPA/Play turning into 0.269 actual EPA/Play in 2002. Every other season in his career, Chad fell not just short but often well short of his expected numbers, including the biggest outlier in the entire dataset, his 0.150 xEPA/Play turning into a paltry 0.011 EPA/Play in 2007, a season which got him kicked off the Jets altogether, an entirely undeserved outcome, which he would quickly prove once he got to Miami. The Jets’ QB room still has not recovered from this move.

We do all know the reason for Chad’s prodigious skill not converting into prodigious results, but we don’t need this to turn into another Herman Edwards bashing session. We’ve had enough of that on my Sports Passion Project already, but now that you’ve seen this, you can perhaps understand the true scope of my hatred for Herm’s style of coaching, if (somehow) that had not come through clear enough already.

This is what can happen when your results continuously fail to live up to your skill level. One of the best QBs in NFL history in terms of skill can completely slip through the cracks, just like Chad Pennington has.

Other notable names (for various reasons) on the career xEPA/Play chart are Steve McNair in 28th place, well above where he’s ranked on most QB lists. Kirk Cousins makes a good showing in 32nd place. Same goes for Bert Jones in 34th. Bobby Hebert is above several Hall of Famers in 37th, and David Garrard manages to make an appearance in the top 50. Jaguars represent.

For most, that would be all. I am 6000 words into an article that should just be a brief description of a table already, but I will not be able to rest until I give you guys just one further application.

When discussing QB skill vs QB results, it always comes back to the fundamental question. The question that started this entire SPP story arc when I asked it about Matthew Stafford back in February.

Is the QB carrying his offence, or is his offence carrying him?

I cannot answer this question throughout all of history, as there was no equivalent EPA/Play measure before 1999, but from 1999 and onwards, it is trivial to compare a player’s xEPA/Play to his actual EPA/Play, in order to get a gauge on whether he was being helped by his offensive environment over the course of his career, or hindered by it.

Note that this is not a direct interpretation. Players can be helped by all kinds of things. Like I said above: turnover luck, weather condition luck, and etcetera, but by and large, the offensive environment a player plays in is the main reason for consistently over or underperforming his skill level. With that said, this is a table featuring all 117 players that have touched the ball a minimum of 1000 times in the play tracking era, sorted by the difference between their xEPA/Play and their actual EPA/Play. A positive difference would imply a player significantly underperforming their skill level. A negative difference would imply a player getting results much better than their showcased level of skill deserves. Sort both directions to find the most overrated and underrated players.

Wait a minute.

You’re telling me that the player very most hindered by his offensive environment over the last 25 years is Bryce Young, right now?

That is exactly what I’m telling you.

Bryce Young is severely underperforming his skill level through two years at the NFL level. In 2023, his -0.047 xEPA/Play turned into a tear inducing -0.178 EPA/Play once all was said and done. In 2024, his much more optimistic 0.092 xEPA/Play only converted into a still uninspiring 0.008 EPA/Play. That’s not a good number in real life, but his 0.092 xEPA/Play put him 22nd in 2024. You can work with 22nd. That’s approximately in line with Drake Maye, and everybody seems to be excited about Drake Maye. We can absolutely still be excited about Bryce Young, if only he could ever stop underperforming his individual skills so much.

In case you think I’m full of it, and that Bryce Young at number one is bogus, how about you flip the table over, and see that the four QBs very most advantaged by their offensive environments over the last 25 years are two Kyle Shanahan guys, one Sean McVay guy, and Colin Kaepernick.

That seems to check out doesn’t it?

To me, this shows the formula is working. If you’re trying to devise a model that claims to show who is the very most advantaged by their offensive environment, you must have the Shanahan and McVay guys there, or it’s a bust. This makes me happy to see everybody firmly in the top four spots in the overrated part of the list, and the fact that all the Shanahan and McVay guys are there makes very notable the one Shanahan/McVay guy who is not there, laying bare just how big of a mistake it was for the Rams to ever let go of Jared Goff.

There is no evidence that Jared Goff is or ever was a product of the Sean McVay offence, but there’s all the evidence in the world that Matthew Stafford has been a product of every offence he’s ever been a part of, making more and more clear every day that Jared Goff plus several draft picks for Matthew Stafford is one of the worst trades in sports history. It’s worse than the Deshaun Watson trade, without question, because it came complete with one of the draft picks already being spent on Detroit’s franchise QB. There seemed to be an idea that the Rams could make another Jared Goff, but nobody made Jared Goff. He was never a product of the McVay offence, and I’ve (indirectly) just spent 7500 words proving that to you.

If you believe in my methodology here, that means you’re with me on this, and it also means that we have to take a serious look at the man occupying the number five spot on the list of players most overrated by their actual results.

However, before I get there, I must say that 1000 is clearly too low of a touch threshold when attempting to talk about underrated or overrated careers. A much more acceptable threshold is 2000, because that gives time for a QB to work their way through multiple cores of offensive players, instead of the list being clogged by many players who only got a chance with one offensive group, which stunk.

Below, I’m going to present you the exact same table as above, only with the minimum touch threshold boosted to 2000 instead of 1000, in an effort to focus mostly on people who have been systematically under or overrated:

You can always tell the personality of the human crafting the data, if you look at his results long enough.

An NFL average QB operates at 0.04 EPA/Play. It’s not quite zero, because EPA is scaled such that the average play is worth zero, and the average QB play is not necessarily the same as an average play in general. I classed players as significantly over or underrated if they could fit an entire league average QB between their actual results, and the results their skill level would indicate.

Isn’t it just the most Sports Passion Project thing ever then, that according to this model, there are 24 QBs in the last 25 years that can be classed as significantly underrated, compared to just five that are seriously overrated? One of those five massive overperformances is Blake Bortles, and nobody truly thinks he’s better than he was just because he got 0.001 career EPA/Play out of -0.041 EPA/Play skills, so it’s really just four QBs in the last 25 years about whom I would legitimately be willing to use the word overrated.

I have said my piece on Matthew Stafford. I was infamously said he’s ‘held back every offence he’s ever been a part of.’ Analysing the data did force me to come around on expanding the playoffs last week, but it did not force me to come around on Matthew Stafford this week. In fact, it’s hardened my stance even more. Matthew Stafford is the most overrated QB of his generation, bar none. Sure Colin Kaepernick overperformed by more, but he only got to 2304 career plays. Amongst players with a real career’s workload, nobody has consistently overperformed his skill level as much as Matthew Stafford has, primarily as a result of the fantastic offensive environments that he’s spent a whole career being a part of.

However, Matthew is not the only person at the party. In terms of his results overperforming his talent level, there is someone right on Stafford’s tail, with his -0.057 difference between skill and result almost catching Matthew Stafford’s -0.062. It’s an unexpected suspect.

It’s Aaron Rodgers.

Looking at it through this skill-based lens, Aaron comes off as nothing more than a very poor man’s version of Steve Young. Much like Steve Young’s sack rate of 94, Aaron finished his career with a sk%+ of just 98, slightly better, but also a CPOE of just 3.2, which is dramatically worse than Steve’s 6.9.

This is the 20th best CPOE of all time, which is why Aaron is still 33rd in career xEPA/Play. That’s Hall of Fame level, but when you break it down to just the basic tools of the trade, Aaron’s sack avoidance could not even keep up with the league average QB during his career. He never paired that with electric rushing production either, so by and large, Aaron was coming to the party with just his arm, and while that arm is the 20th most accurate arm of all time, and enough on its own to make him a Hall of Fame player, he is neither an inner circle Hall of Famer, nor an immortal of the game, once taken out of the sweetheart Green Bay situation that he spent his entire career in.

People love to talk about how the Packers never picked a WR in the first round during Aaron’s tenure, but people (especially Aaron defenders) love not to talk about how elite the Green Bay receiver room was at almost all times during his career there. If you really look at it, Aaron spent two seasons on the Packers without an elite receiver (2015, 2019), and maybe a third, which depends on where you think Davante Adams was on the totem pole in 2017.

If you take a look at Aaron’s results in 2015, 2017, and 2019, they are not very pretty. They’re actually much closer aligned with his career xEPA/Play of 0.134.

Ain’t it funny how that happens?

For the whole rest of his career though, Aaron had at least one elite receiver. Most of the time he had two (Driver and Jennings, Jennings and Nelson, Nelson and Cobb, Nelson and Adams, etc.), and once taken away from an off the charts receiver room in the late 2010s, Aaron generally performed in line with his xEPA/Play.

For one final time, Aaron Rodgers is absolutely a Hall of Fame player, based on what he did bring to the table, but I’d be lying if I said I wouldn’t like to see what somebody like Chad Pennington, Ken Anderson, or Jeff Garcia could do, if so consistently blessed with the environment to succeed that Aaron was blessed with.

We’ve all heard a million times somebody call Aaron Rodgers the most talented QB there’s ever been, or at least some variation of that phrase, but it’s a dog whistle. When somebody says that, they are revealing themselves as somebody who takes a very arm-centric view of the world, because in terms of sack avoidance, Aaron was not even average over the course of his career. In terms of rushing, Aaron was above average, but nothing historically relevant, and in terms of the ability to make the throws, he was all-time great, but not a GOAT candidate.

In terms of physical talent, Aaron had it all, but in terms of converting this physical talent into actual skill to play the QB position, Aaron did it at a borderline Hall of Fame level in my opinion. His results dictate that he must walk in on his first try, but his individual skill does not. Give a ton of credit to the Packers front office for always finding Aaron elite receiving options to play with, that bridged this borderline HoF guy into an inner circle HoF guy.

Tom Brady is also in the overrated section, but does anybody want to hear me call Tom Brady overrated any more than I already have? I’ve done that a lot on here already, but here are the cliff notes for someone that hasn’t heard it before.

Tom’s career sk%+ is 114, which is all-time great but not a GOAT candidate in this skill, and this is what he was best at. The rush contribution is basically nil, and his career CPOE is just two flat, only 44th all time. Much like Aaron Rodgers is a Steve Young for poor people, I consider Tom Brady to basically be a strictly worse version of Dan Marino.

Tom coasted on the same thing that Aaron did, receiver groups that were almost uniformly elite at all times from 2007-2014. They got quite spotty after that, but all of Tom’s best seasons came in this 2007-2014 window, which is not at all coincidental.

In an effort to end on something positive, I did want to talk about Brian Griese for a minute. This is a man with a career CPOE of 2.5, and a career sk%+ of 100, yet he put up results well below the QB average of 0.04 EPA/Play through his career. This comparison may sound like sacrilege to some, but Brian Griese was basically working with the same set of skills Ben Roethlisberger was working with, and while Ben was able to convert his 0.117 xEPA/Play into 0.130 career EPA/Play, Brian’s 0.116 became just 0.018.

In Brian’s case, it was not an issue of offensive environment, as he had plenty of elite receivers and spent a lot of his career under Mike Shanahan. In this case, it was a career long bout with turnover luck. Despite a career CPOE healthily above average, Brian’s career INT%+ is just 94, which is almost unimaginably low for a player with throwing accuracy of this calibre.

Throwing accuracy and INTs do not have a one to one correlation, but it should be reasonable to expect that a man with a career CPOE as high as 2.5 bring with him turnover avoidance at least above average. That’s basically what Ben Roethlisberger did, and that is why these two are so radically different in terms of career results, despite being such similar players. Turnovers are a result. They are not a skill, but if Brian Griese could’ve improved just a little bit in this area, things could’ve looked a lot different in his NFL career.

Also on the underrated list is a second appearance in this article of Chad Pennington, the all-time great QB that wasn’t, and interestingly, Josh Allen comes in 11th place among underrated players. Even with as great as his results have been, they lag significantly behind his career xEPA/Play, indicating that if he were in a better environment, his numbers would be even better, and for one final stanza, despite being a part of the greatest show on turf for a little while, Kurt Warner’s results are actually understated in a career sense, because he spent more than half of his plays on Giants and Cardinals teams that, despite his best efforts, could not get out of their own way most of the time.

Finding a way to call Josh Allen and Kurt Warner underrated players is something that could only happen in an exercise like this.

There are countless other stories to dig through here of under and overrated players, as well as stories to dig out of every other table that I’ve given the world access to today, but I think that I’m finally done digging for you. From here on in, I’m going to leave the digging to you.

I challenge you all to do some digging for yourself, and find yourself a story that you can tell. I’d love to hear them in the comments, if you’d humour me. If you’d like a suggestion, how about Hall of Famer Terry Bradshaw ranking 123rd in career xEPA/Play, behind Steve Walsh? That sounds like an interesting one, but dig beyond that. Look for an angle involving your favourite team. Look for an angle involving your favourite player. Look for something interesting in the over and underrated lists.

I look forward to hearing what you think.

Thanks so much for reading.

I saw someone's Top 10 QBs for 2025 list and wanted to compare it to xEPA/Play. Played around with a weighted average of the past 3 seasons (with most recent weighted more heavily) to construct a Top 10 (Jackson-Allen, Mahomes-Hurts, Purdy-Burrow-Tagovailoa, Prescott-Murray-Love, depending on how you weight the average and whether you take into account whole career instead of just the past 3 seasons).

Then I decided to expand it out, and found a PFF article ranking all 32 projected starting QBs posted this week. Ranking just based off Career xEPA/Play (without enforcing a total play cutoff), here were some of the biggest differences in rankings between PFF and xEPA/Play:

1. 17 positions away--Matthew Stafford (PFF rank: 7; Career xEPA/Play rank: 24). I get it a bit more now why you bring up Matthew Stafford as an example so often. He's still being ranked as a top 10 QB by PFF?? I also note that this could be an even bigger difference depending on where we slot the 4 QBs on PFF's list that do not have a qualifying xEPA/Play season. I've just chosen to leave them off, but if we put them in about where PFF has them in the rankings (not a wise move, but one that plays by their rules), McCarthy, Penix and perhaps even Ward would slot above Stafford. It's not even as if Stafford has seen a clear shift in how well he's been playing recently compared to his career norms. I could understand keeping him higher than 24, but top 10 seems ridiculous to me.

2. 15 positions away--Bo Nix (PFF rank: 19; Career xEPA/Play rank: 4) Sure, with only one (pretty good) season in his career, xEPA/Play is probably overrating him for now. I don't really put a lot of stock in that 4th place position, so discounting him somewhat is understandable. What's less understandable is the difference in treatment between Nix and Daniels under PFF's rankings. PFF puts Daniels at 6th, while Nix is down at 19th. There's a results-bias here (as Daniels had 0.202 EPA/play vs Nix's 0.090 EPA/play), but in terms of skill as measured by xEPA/Play, they are neck and neck (0.162 for Daniels vs 0.164 for Nix). Perhaps PFF grading is more results-oriented than I had thought--but they do acknowledge that after his first four starts, Nix was the 6th-best graded quarterback in the league. I guess I don't understand how you can acknowledge that level of sustained performance and still keep Nix this far down on your rankings.

3. 13 positions away--Russel Wilson (PFF rank: 22; Career xEPA/Play rank: 9). This one I think is more understandable, as Wilson is probably being propped up in career rank by all his good Seattle seasons and he's probably on a decline in his career. I think probably PFF is underrating him a bit, and career xEPA/Play is probably overrating him a bit in this ranking.

4. 13 positions away--Mason Rudolph (PFF rank: 31; Career xEPA/Play rank: 18). Based on their blurb, the PFF ranking seems more about the perception of Rudolph as a backup quarterback being ranked amongst starters than about his production or skill. I think that does a disservice to Rudolph, though, whose career xEPA/Play is actually higher than Trevor Lawrence's (perhaps partially due to only a couple of Rudolph's seasons qualifying--although their traditional rate statistics are remarkably similar, too, so it's not just that Rudolph has played poorly in seasons that he doesn't qualify for xEPA/Play). Listing Lawrence at 16 and Rudolph at 31 seems too strong a penalty for being a backup. When you factor in the number 1 overall pick (and generational one at that) vs 3rd round pick, though, it starts to make sense in the general perception of these players and speaks to the point you’ve made recently about draft position mattering.

5. 9 positions away—Baker Mayfield and CJ Stroud (PFF ranks: 13, 14; Career xEPA/Play ranks: 22, 23). Grouped together because they are next to each other on both lists

6. 9 positions away—Joe Burrow (PFF rank: 2; Career xEPA/Play rank: 11). Burrows’s ranking in terms of career xEPA/Play is lowered a bit by the inclusion of Nix and Daniels since we’ve removed the total plays threshold. That said, I do think he tends to be a bit overrated in NFL discourse, which generally puts him as a top 5 QB, where I think he belongs more in the next 5 Qbs.

7. 9 positions away—Joe Flacco (PFF rank: 29; Career xEPA/Play rank: 20). He’s buoyed a bit by his best seasons in Baltimore in terms of Career xEPA/Play, but the major discrepancy between the lists is the inclusion of a bunch of young passers (McCarthy, Penix, Ward, Stroud, Young, Williams) who either haven’t played before at the NFL level or whose skill doesn’t remarkably surpass what Flacco has demonstrated even just the past couple of seasons. He’s on the downhill of the aging curve while they are just coming into their own, but it wouldn’t surprise me if these rookies end up playing worse than Flacco this season.

I've been looking at this data on and off for the past week and every time I do I find something fascinating (to me anyway). Really excellent work.

Take Colin Kaepernick for example. He goes from having the 100th best season by xEPA/play at the beginning of his career to having the ~150th worst four years later. Every year is worse than the one before (except for a slight rebound from horrific to just bad in his last year). This is not a normal career trajectory. Most quarterbacks either get somewhat better or stay constant. (Unless they play long enough to fall off the aging cliff.) Looking at this it's obvious why no team thought he was worth the drama hiring him would bring.