What Netflix Didn't Tell You About Steve McNair

Netflix left out a lot regarding the life of Steve McNair, and why his death is so heartbreaking. Allow me to fill in their gaps.

(No subscribe buttons on this. No links to other posts. No self promotion whatsoever. This is dedicated to the memory of Steve McNair. Enjoy)

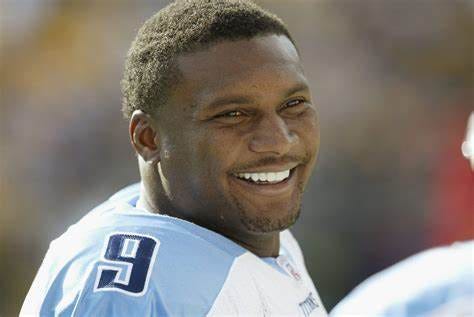

Just recently, Netflix released a one hour long documentary, titled 'The Murder of Air McNair.' It was an okay watch, but it irked me as a football fan, for one very simple reason. Do you know what there was very little of in this show?

Steve McNair.

This was not really a sports show. It was a documentary about the murder of a celebrity, and some quirks of the investigation. The actual identity of the celebrity proved immaterial. It reminded me a lot of an old CSI episode about a fake murder of a fake celebrity. Considering this killing was real, that is not a compliment.

You can find a million docs just like it on the same platform if you care to search. I think this is the worst Untitled (what Netflix calls their series of documentaries on sports people) that they've ever done, and it's not fair that fate has to befall a man like Steve McNair.

In the documentary, they detail the Houston Oilers (the team that drafted Steve) moving to Nashville, where they go undefeated at home in the first year, go on a run all the way to the Super Bowl, and nearly win it, all in their first season in their new city (having played in Memphis and in Vanderbilt Stadium their first two years as Tennessee). Later on, they mention (with no context or detail) that Steve eventually won a league MVP award, and that is all the football discussed.

From here, the doc will have you believe that the city instantly accepted Steve. They want you to think that everything was perfect, until that horrible day on July 4, 2009.

In so doing, they leave out what are critical elements to the story, and they (deliberately or otherwise) undercut the difficulties and triumphs of a man who should've never been able to win an MVP award. This is irresponsible on their part, but since they won't tell the story correctly, allow me to do it for them.

Steve was a trendsetter.

He grew up in rural Mississippi, raised by a single mother without the appropriate funds to do so. One of five brothers, during Steve’s NFL career he often publicly looked back, remembering his thoughts about watching his mother Lucille McNair break down in tears, thinking that due to her low income level she could not raise her boys properly. To try to give her boys everything she could, Lucille went without a lot of things in life, and you can tell by watching and listening to the tone of voice on interview clips (you can find them if you look hard enough) that this memory hurts Steve to recall.

After overcoming this all to be a star athlete for Mount Olive High School, finishing his career as a Mississippi state record holder in many passing categories, he was recruited by all of the big division one schools to play football.

If this had happened in 2024, Steve would've been a five star QB prospect. Big schools would be offering him millions of dollars to come play for them. Unfortunately, like many highly athletic black QBs from Steve's part of the country in this time period, big schools thought they could leverage his poor financial circumstances into forcing him to change positions. In Steve’s case, teams wanted him to convert to defensive back.

You may ask: why would teams want such a clearly gifted QB to play defensive back?

This is 1991. Black men don't play Quarterback.

As of this point in history, there still exists a stigma against black men playing the QB position. Warren Moon has just ranked first on my QB tier list for 1990, but he’s never had any significant playoff success, which is the only thing that will change anybody's mind.

Even in the regular season, the NFL at large can claim that success is rare for black men at the QB position. As of 1990, there have been just two black men to rank in the top ten of my QB tier list ever. Doug Williams has done it three times, in 1981, 1982, and 1988. Warren Moon (as of 1990) has also done it three times: 1988, 1989, 1990. From 1970 to 1990, there are 210 top ten positions available, and only six of them are occupied by black men. Success is rare.

Like many statements with regard to race relations, this is a falsehood wrapped in a technical truth.

I'm not ignorant to the fact that black people have succeeded so little only because they've been given so little chance.

Doug Williams was only given his chance because of legendary coach Joe Gibbs (then the OC of the TB Buccaneers) sticking his neck out in a big way in order to make it happen, and upon ranking third in my 1981 tier list, and 7th in 1982, Doug was forced out of the NFL, as no team would pay him like a starter, and he refused to start for backup money. In today's terms, that's like all the owners telling Jalen Hurts that he's just not good enough to be paid like a starting QB.

That's how much the NFL did not want a black man to be playing this well.

Warren Moon only got his opportunity because he'd just thrown for 5000 yards (the first professional QB ever to do so) and won his fifth championship in a row for the CFL's Edmonton Eskimos.

Eat your heart out Tom Brady. Five in a row.

It was getting a little ridiculous for the NFL to continue telling him he wasn't good enough after that much winning. Five championships in a row still only got Warren offers from two teams, but his foot was in the door, and you know the rest.

The stories of these two men are both iconic in NFL history, but both got their opportunity based on a lot of things going correctly, and both easily could’ve drowned under the belief that black men can’t play QB, in the same way that so many great black QBs that we never got to play professionally did.

All of this finally began to turn at the 1990 NFL Draft, when the Detroit Lions made QB Andre Ware the seventh overall pick. The first black QB selected in the first round since Doug Williams in 1978, and only the second one ever. However, Ware was never given a chance to succeed. His NFL career consisted of six starts for the Lions, and he never got another chance after that.

Andre thought this was fishy, and he's not the only one. This is a seventh overall pick quarterback. Imagine if after his four starts in 2023, Anthony Richardson never got another chance (not even at a backup job) in the NFL. Wouldn't that feel fishy to you? Teams normally give chance after chance to their top ten draft pick quarterbacks, yet for Andre Ware, it was six starts and the NFL had seen what it needed to see from him. All of this about ten years after the last black QB drafted in the first round (Doug Williams) was forced out of the league, despite clearly being a top ten QB.

Coincidence? I don't think so.

That leads me to the third black quarterback selected in the first round of the NFL draft, ever. His name is Steve McNair.

Steve is one of the original Josh Allen types. He was drafted third overall in 1995 because of his immense talents at the QB position, but seen as a risky draft choice at the time. This is partly because of his skin tone, but also partly legitimate. There's no doubt Steve's skills are quite raw, and his competition playing for HBCU Alcorn State is seen as weak compared to division one competition. Think of Josh Allen in 2018 as I say this. All the same criticisms Josh faced coming into the draft are the ones that Steve faces in 1995, but Steve must also climb the mountain of being a black QB, in a league that still doesn't take those very well.

Due to all these factors, Steve sits, not ready to play at the NFL level in 1995. This was likely the right choice for both Steve and the team, but when he also sits out all of 1996 for a Houston Oilers team that is not getting any better, and watches Kerry Collins (drafted behind Steve in the 1995 Draft) playing well and playing in the NFC Championship in just his second season, and perhaps remembering what happened to Andre Ware before him, Steve throws a serious temper tantrum.

Are the Oilers going to play him, or not?

This proves what needs to be proven to Jeff Fisher, and from here on Steve will be the Oilers' starter. Unfortunately, at precisely the same time this is happening, the Houston Oilers, and their fans that (eventually) embraced Warren Moon, are moving to Tennessee, to play in Memphis in the interim before a permanent move to Nashville, in front of fans that will not embrace a black QB nearly as easily as fans in Houston did. This is not a racial issues Substack, so you can look up Memphis's race issues on your own time, but be aware of them, and be aware of how they could have derailed Steve McNair’s NFL career.

This can’t have been easy for Steve. In 1997, the team does not get any better. Steve plays okay, but not fantastic. Racial slurs are common to hear, playing in the former Jim Crow South, etcetera.

1998 is much better, with Steve individually ranking in my top ten QBs list for his very first time, and throwing for 3000 yards for his first time, but the Oilers stubbornly refuse to get better. The team goes 8-8 for the third season in a row, but here comes the big one.

In 1999, the Oilers become the Titans, and the magic happens.

The 1999 Titans are one of the luckiest teams in NFL history. They turned 9.16 Expected Wins into 13 real ones. That’s 3.84 wins above expected, the fourth highest in the play tracking era (1999-present). It was also a down year for Steve McNair individually, largely due to missing five games with the first in what will become a long string of injuries, but it also shows the unbelievable toughness that will become Steve’s hallmark as a player.

Before week two against the Cleveland Browns, Steve ruptures a disk in his back. In 2024, this is a season ending injury, with doctors advising no contact for six months. In 1999, Steve came back after just five weeks, because he knew he had to. I dislike continuing to play the race card, but black QBs are held to different standards. This truly begins to die with Randall Cunningham’s epic 1998 season, but change is slow.

Steve is perfectly cognisant that his starting spot may not be there for him after a whole season out, and the Tennessee fans will not be clamouring to see him back, for reasons that everybody (player, coach, organisation) knows, but are not comfortable talking about publicly, so he comes back way too soon.

This back injury will never heal properly. He will have issues getting around for the rest of his life because of it, but he keeps battling, and this is where we get to a truly heartbreaking moment in the story.

Upon coming back to a team that’d gone 4-1 in his absence, there is an ugly 17-0 loss to the Miami Dolphins. It’s probably the worst game of Steve’s NFL career, but in the facility the next day, he sees a package for him. A package being there to meet you on Monday morning means it had to have been shipped overnight. Those of you who worked with the US mail back then know what it’s like to try to ship overnight on a Sunday in 1999, so Steve gets excited to open it. What could’ve been so important?

What he sees is a disgusting tirade full of racial slurs, indicating that this particular fan was perfectly happy with Neil O’Donnell as the starting QB.

Steve doesn’t share the note with anybody. He simply crumples it up and throws it in the trash, not sharing the story with the media until several years afterwards.

That so much time, effort, and expense (overnight shipping in 1999 is not cheap folks) was taken just to try to knock him down even further had to give Steve second thoughts about risking his long-term health with this back issue trying to get back faster, when this is the thanks he gets.

Nevertheless, after getting that note, the Titans win ten of their next 11 games, which brings them all the way to the Super Bowl, where they are hopelessly overmatched against one of the best NFL teams of all time in the 1999 Rams. In this game, Steve plays very well, and comes just one yard short of likely the biggest upset in Super Bowl history (2007 has not happened yet).

That story about the overnight note is private, not shared with anybody, but there is another, very similar moment right at the beginning of the 2000 season. This one is not private. We can all see for ourselves. In week two against Kansas City, Steve goes down with yet another injury. He’s carted off the field, and the crowd cheers.

This is not the ‘thank you for your service’ kind of cheer that injured players often get. This is a ‘Neil O’Donnell sucks, but we’re still happy to see him instead of you because he’s white and you’re not’ kind of cheer, and Steve knows it.

He will never forget either the note or this cheer. Steve cites them as the two moments that he was never able to let go of from his time playing in Nashville. While Steve McNair and the city of Nashville will eventually grow a begrudging respect for each other, these two moments will always stain the relationship between the two of them.

Over the succeeding few years, Tennessee will never get back to the Super Bowl. They’ll get back to a few AFC Championship games, but will lose all by multiple possessions. In 2001 Steve, despite not being able to practice due to injury, often having to be helped off of planes due to his bad back that has never healed, will have his breakout season, transforming into the top five QB you remember, as the Titans finally get him a top receiver in Derrick Mason.

The offence improves dramatically, but the defence (at one point not very much worse than the highly heralded 2000 Ravens) regresses in an extreme way, meaning the Titans have fallen behind as a team, despite their QB being better than ever. Steve has been a top five QB multiple times by the end of 2001, but due to the winning and the elite play never happening at once (and perhaps some other reasons too), he has not made a Pro Bowl in any of those seasons.

The Titans make the AFC Championship again in 2002, but fall just short to the Oakland Raiders, which really drives the point home that the Titans are not what they once were, because Tennessee always had Oakland’s number in that forgotten early 2000s AFC rivalry. The headline in the NY Daily News’s Monday morning coverage of the AFC Championship game says it perfectly:

McNair Just Outnumbered

This is more or less the state of affairs going into the 2003 season. Over the past four years, Steve has battled back injuries, rib injuries, shoulder injuries, toe injuries, throwing thumb injuries, and issues with his sternum, but in the 2003 offseason, he feels healthier than he has since 1998.

There is a common problem in Steve’s NFL career (except for the year 2000). One man trying very hard to drag inferior surroundings into competition against real teams. He is mostly able to accomplish it in his brief spurts of relatively good health, but things begin to fall off in the all too common injury riddled parts of seasons where he is well below his best.

Throughout the 2003 season, Steve will battle calf and ankle injuries, and end the season as a man on two bad legs, but nevertheless lead the NFL in EPA/Play, and ANY/A, and win a well deserved MVP award. More details on this legendary season will be forthcoming in Steve’s His Year article entirely focused on his 2003 season, which is being released tomorrow, so I will stop short of giving any further spoilers on that.

What’s more important for this article is that Steve McNair has just cemented the fact that he’s broken two crucial glass ceilings. He’s the first black QB, and only the second black man who does not play RB (Lawrence Taylor) ever to win the NFL’s MVP award, and he’s also the first ‘mobile’ QB ever to win an MVP award.

Prior to Steve McNair coming on the scene, people thought of both black QBs and ‘mobile’ QBs as being fundamentally limited. Warren Moon was a great NFL player, but he never won anything they said. Randall Cunningham was just a glorified running back they said, but no more.

Steve McNair has been to a Super Bowl, and nearly won that Super Bowl. He’s been to two additional AFC Championship games, and spends most of his career as the NFL’s winningest active QB on a per game basis. He’s done it all while being a victim of racism from power five colleges, NFL scouts, police in his city (who often follow him around town, looking for any excuse to pull him over), and his own fans, still not ready to accept that a black man could be top of the line in this league.

Again, it’d been done before, but when Doug Williams did it, he got forced out of the NFL. When Warren Moon did it, people cried about the lack of winning. When one team finally caved and drafted Andre Ware as a black man in the first round, he was laughed at, never given a real chance, and forced out of the NFL before anybody could see if he could count himself among those two greats above.

Steve McNair opened the floodgates. It was his talent (with help from Randall Cunningham) that finally opened the doors to teams selecting black QBs in the first round, starting with Daunte Culpepper and Donovan McNabb in 1999, moving quickly from there to Michael Vick being the first black QB to be selected first overall in 2001.

Before any of these men could take centre stage (like they all eventually would), there was still time for the OG to slip in and collect his one MVP award. The one MVP award that opened the door for everybody to walk through behind him.

Steve’s NFL career was mostly over after that. More chest injuries would happen in 2004 to keep him out of most of that season. He would make it back for 2005, but it wouldn’t be the same. At the end of the 2005 season, the Titans would (literally) lock McNair out of the facility, not allowing him in for offseason workouts or treatment or anything, in an elaborate ploy to get him to accept a lowball contract renegotiation.

What reward for a man who had given everything to the Tennessee Titans for ten years.

Much like 1991, when faced with all of the power conference college offers being conditional on changing positions, McNair stood up for himself and refused, and good on him for doing it. Eventually the league stepped in and mandated a trade to Baltimore, where he would make more money in one year than the Titans were offering for three.

By this point he was much more of a game manager than the playmaker he’d been, but he still managed to post a 0.108 EPA/Play and a 3.2 CPOE as the fix at QB the Ravens had been looking for since before they even became the Ravens.

Not bad for an old guy with a bad back, bad right leg, bad left leg, and trouble breathing as a result of all the chest injuries. Not bad at all.

After this one comeback season, Steve McNair’s NFL career was over. He simply had nothing more that he wanted to give to this game, but he had already given so much.

Bryce Young owes a lot to Steve McNair. Lamar Jackson owes a lot to Steve McNair. Josh Allen owes a lot to Steve McNair. The NFL owes a lot to Steve McNair, because he broke several glass ceilings, all at once. In one NFL career, he proved having a black QB can work. He proved mobile QBs can work. He proved FCS QBs can work. He proved very raw QB prospects can work if given the proper time to grow and mature. If you excluded all the modern NFL QBs who could be described as black, mobile, FCS, or ever were seen as a raw draft prospect, who would you have left?

That’s what Steve McNair did for football.

It’s not fair for one man to carry all of this pressure on his shoulders, but African Americans know that one bad egg will soil the whole bunch. Be it football (in the 1990s), business, or whatever field you’d like. If one black man gets a chance in a field (like the NFL) where all the money is controlled by white people, and he blows it, it will be a while before another black man gets a chance. All carry this burden in service of each other.

That is why Steve McNair couldn’t convert to defensive back. That is why Steve McNair had to play through so many injuries. That is why Steve McNair couldn’t accept lowball contract offers. If he’d done any of these things, it would’ve created a reputation for all of the people coming behind him. For instance, imagine if the spectacular flameout that was Michael Vick in Atlanta had happened before Steve McNair, instead of afterwards. It would’ve been years before another young athletic black man was given the chance to play quarterback.

Steve McNair protected everybody from all of that.

That’s why July 4, 2009 is so tragic.

For a man who spent his whole professional life trying to kick off the stereotypes that so aggressively followed him, just how evil is it that the young successful black man was found dead, well before his time, by four gunshot wounds?

It’s sad. It’s incredibly sad.

It’s so sad that people don’t even know how sad it is, and I (naively) thought Netflix was going to teach people about it. Even I was excited to see what they had to say, but there was not a word about it in the entire hour of this show. They treated Steve McNair like a nameless faceless celebrity designed for the plot of a CSI episode, and for a man who broke so many barriers as a football player, that’s not right.

Hopefully I’ve done whatever part I can to do justice to the memory of Steve McNair. Click back tomorrow for more details on the football player that Steve was, and thank you very much for reading.

I remember him well.