My Replacement For Passer Rating

Passer Rating is a statistic the NFL has used for years, and still gets referenced today. However, it is outdated, and I plan to fix it.

Before we begin, I’m going to ask you a question. Does anybody care about Passer Rating anymore?

If the answer is no, then perhaps there’s no reason to continue reading, but if the answer is yes, then I’m about to really improve your understanding. You’ll like this.

Passer Rating is a statistic that is as old as the hills in the NFL. It’s been used since its invention in 1973 as the NFL’s official tool to evaluate QB play. Due to its status as being invented by the NFL itself, the league still pushes it and it still gets used on game broadcasts to this day, despite being pretty outdated for the modern game.

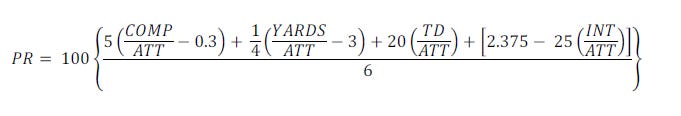

The biggest pro of Passer Rating is that we know how to calculate it. The formula is as follows:

Now this may look complicated, but all this is doing is combining five statistics (pass completions, passing yards, passing touchdowns, passes intercepted, and passing attempts) into one number that tries to evaluate Quarterback play.

It was created this way because prior to this system being invented, the NFL was deciding good QB play from bad based on a composite ranking of how QBs performed in these five statistics. For instance, if a QB had the highest completion percentage (ranked first), highest yards per attempt (1st), most touchdowns per attempt, and fewest interceptions per attempt, their score would be four, as they ranked first in all four stats, and this would obviously be the best in the NFL.

There are several problems with this, primarily that the scale makes absolutely no sense. If a player ranked third in all four stats, their score would then be 12, three times worse than the player with the score of four, but it’s entirely possible that the player is only slightly worse. Additionally, the main reason for ending this system was that it was complicated and difficult to understand. Composite ranks require knowing where a player stands in four separate statistical categories, which quite frankly is difficult to report in a newspaper. At the time, this was a big deal.

This is the first thing we need to understand about passer rating. The entire purpose of this stat’s existence is to dumb down QB analysis to a level where even newspaper reporters of the 1970s could get it.

Continued confusion would not do, so in 1973 the Hall of Fame convened a statistical committee to create a new number with which to evaluate QB play. It was important that the end result was one number, and that it would be on a scale understandable to the general public. This generally meant no decimal numbers, and no players being multiple times better than others. People wouldn’t get it. Simplicity was the be all and end all, which also explains the odd weights and additive factors in the formula:

All individual factors were designed so that an average season would result in a one, and an outstanding one would result in a two. For instance, if a season were to result in a completion percentage of 0.5, which is 50 percent (not bad at all for a QB in the 1960s, which is what they were looking at when creating this statistic), you can plug 5*(0.5-0.3) into your calculator and see that you get exactly one. Do the same exercise with 70 percent and you get two, etcetera. The same goes for every factor here. Seven yards per attempt results in one. A touchdown every 20 attempts results in one, and it’s about the same for interceptions.

The stat ranges from zero to 158.3, and you may wonder why that is. Allow me to explain. It’s simpler than you think. The creators of the stat just wanted 100 to mean outstanding. To them, this meant scoring about 1.5 in every category, the midpoint between okay and outstanding, because they thought being good at everything makes you outstanding on the whole, which is actually a philosophy I agree with. Adding 1.5 in every category leaves you with a score of six in total, which is why the stat is divided by six and multiplied by 100.

The scale is entirely arbitrary. They could’ve made the top score 9000 just as easily. The creators simply wanted 100 to be the mark of an incredibly good player so that people reading the newspaper in 1973 would understand. Why they didn’t just bind this stat to always be between zero and 100 I have no idea, but perhaps in 1973 statistical indexing is not as common of a practice as it is now.

Now that we understand what the statistic is, what it was for, and why the formula looks like it does, we have to confront the elephant in the room. I’m 748 words into this exercise and creating a good statistic has not yet been mentioned as a motivation for anybody.

It was, but it was not the primary one, and this leaves some holes that still exist today.

First and foremost, the statistic was created by people watching football in the 1960s, and as a result reflects 1960s priorities of playing the QB position, and simultaneously makes some guesses about the future of the game that turn out to be incorrect.

You see, the way these weights work has not gone in conjunction with how the game has evolved, and I’m going to give you an example. Recall how I said seven yards per attempt got you a one (designed to be perfectly average) in that specific category? This has actually held. The average NFL QB today will also score around seven yards per attempt (Derek Carr’s 7.1 fits well here). However, I believe that the makers thought something that turned out to be wrong. They thought yards per attempt were going to skyrocket in their very near future (through the 70s), which turned out to be absolutely incorrect.

We’ve actually just seen the post-merger NFL record for yards per attempt in a season, with Brock Purdy’s 9.64 in 2023 beating out every QB ever with at least 400 pass attempts in a season. Plugging this into the passer rating formula sees Brock get a 1.66 in this category.

Uh oh.

You may be wondering what the problem is, but recall I said that in a specific category that a player was supposed to get a two for being absolutely outstanding. In fact, the best any player has ever done in the post-merger NFL can only muster a 1.66. To get the full two points in the yards per attempt criteria a player would have to average 11 yards per attempt, which is and has always been entirely unachievable. Therefore, even though players are (in theory) supposed to be graded between zero and two, in the yards per attempt category it’s really between zero and 1.66. The stat makers messed up pretty badly here, and it’s never ever been fixed.

The reason this gets brought up first however, is that with all we know about football in 2023 compared to 1973, a mistake that makes raw yardage by far the least important component of the all-encompassing QB number actually makes a statistic better, not worse. Perhaps the 1973 statistical committee knew this, and I’m not giving them enough credit. I’d like to think that, but in reality I’d like to think this was just a bad guess on their part.

It is not the last of the bad guesses.

This is where we get into the real issues about how passer rating is not adequately prepared to deal with the modern game, beginning with completion percentage.

The modern revolution towards higher completion percentages is something the passer rating formulation is entirely unprepared to handle. I said before how the placeholder for average yards per attempt (seven yards flat) still holds today, but the presumption of an average completion percentage being 50 percent was outdated as soon as 1980, and by now is such a foreign concept that we modern fans cannot even understand how an offence working at a 50 percent completion percentage would even operate.

The best yards per attempt figure of all time can muster just a 1.66 on its scale. To reach a 1.66 on the completion percentage scale, all one must do is reach a 63 percent completion rate, which is something most NFL QBs can do, throwing the scales all out of wack.

The touchdown marker (one touchdown pass per 20 pass attempts being average) actually turned out to be really harsh, as the league would routinely have years before the 2004 explosion in passing where fewer than five QBs would hit this benchmark, and even in the modern game an average QB cannot manage a 5 percent touchdown percentage, with average being about 4.5 these days, but the biggest misfire of all is how the creators decided to scale interception rate.

They decided that an average QB would throw an interception on 5.5 percent of all pass attempts, which turned out to be so immediately wrong that I struggle to understand how it didn’t bring this statistic into immediate disrepute. In the year the stat was introduced, only four (four in the entire NFL is not average) people threw interceptions this often, and it only got more wrong from there.

As soon as 1990, no QB at all was worse than this 5.5 percent benchmark. Therefore, Passer Rating has been implying that since 1990 every QB in the NFL has been above average at avoiding interceptions, which obviously cannot be true. If everybody is above average, you have set your average incorrectly. In addition, two on the scale is supposed to be outstanding, but it only takes a 1.5 percent interception rate to get yourself a two on this scale.

In 2023, six different people (CJ Stroud, Kenny Pickett, Justin Herbert, Lamar Jackson, Derek Carr, Dak Prescott) hit the 1.5 or better benchmark, and this is in the new NFL where people are slowly starting to realise that turnovers are not all that bad. If we go back to 2019, it’s ten people throwing interceptions on 1.5 percent or less of their pass attempts. If ten people can achieve what’s supposed to be outstanding, and barely achievable, then evidently our scale is wrong.

Therefore, the scale is not entirely correct in any of the four factors. Yards per attempt and touchdowns per attempt are both far too difficult (nobody has ever scored two in either). Completion percentage and interception rate are both far too easy (people score two all the time in the modern NFL).

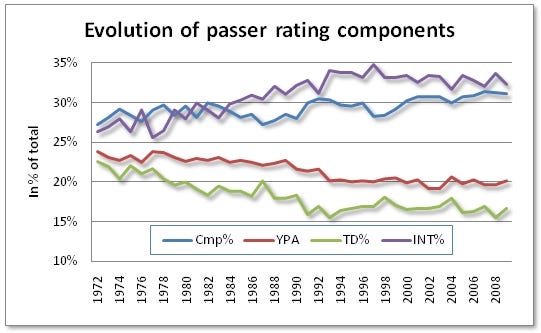

Considering Passer Rating in the end involves a multiplication, it prefers bigger numbers so it can multiply those bigger numbers, and cause exponential increases. Therefore, since all factors are weighted equally in the Passer Rating equation, it biases heavily towards the two categories that can generate the highest numbers: completion percentage, and interception rate. The relative importance of all four factors is shown below:

This is the main problem with Passer Rating. It is not the catch-all stat that it likes to think it is. It likes very low interception rates and high completion percentages (in that order) above all else, and will throw you a bone for lots of yards and lots of touchdowns if you’re in need of a tie break.

This is how we end up with a stat that thinks Brock Purdy, Dak Prescott, Kirk Cousins, Lamar Jackson, Tua Tagovailoa, who are all totally legit, but also CJ Stroud, Jake Browning, Russell Wilson, Jared Goff, Derek Carr, Jordan Love, Baker Mayfield, and Justin Herbert, who are all totally not, were all better than Patrick Mahomes in 2023.

It’s ludicrous to say 13 names before getting to Patrick, even in a down season where I ranked six QBs better than him on my tier list, but Patrick just doesn’t run the Passer Rating grift. He’s not nor has he ever been the most accurate passer in the world, and these days he throws more interceptions than most. Based on those two things (and them alone) he is not in the top ten QBs of 2023 according to Passer Rating.

Is this really how we should be grading our players?

I will give PR its due. It was designed to be simple and to have people see a three digit number and say ‘wow. That guy must be great.’ It accomplished both those things, but failed to accomplish almost anything else in terms of telling the public how good players are. I will go into detail as to why, and then attempt to accomplish those things myself by creating a better version of this statistic.

First and foremost, I have to give Passer Rating just one more bit of credit before I commence tearing it to shreds.

It is called Passer Rating. It is not called Quarterback Rating. In technical terms, it does not claim to be able to tell you how good a QB is, and its technical interpretation should be that it’s telling you who the best QBs in the league are given that a pass is thrown.

Passer Rating ignores the skill of avoiding sacks entirely, and it also entirely avoids any damage QBs can do with their legs. It does both of these on purpose by the way, because including them makes no sense due to the assumption that a pass is being thrown (meaning it’s guaranteed that there is no sack and no rushing attempt) that comes inherently with the interpretation of the statistic. It’s not the stat makers’ fault that fans interpret their statistic incorrectly to mean something it doesn’t mean, but given the catch-all nature to the casual fan that the number eventually took on, I think it is time to start acknowledging this for the flaw that it is.

A good catch-all QB stat should take into account that there are lots of outcomes in which a QB plays a part that don’t involve a pass being thrown (mostly their rushing attempts, sacks, and non-interception turnovers), and in the case of some, these outcomes are their most valuable skill. Ignoring these outcomes altogether is the same as deliberately ignoring an entire facet of playing the position like passer rating does.

Additionally, fixing Passer Rating also involves taking it from beyond the archaic component statistics available in 1973 and into the new millennium. We all now know that completion percentage is not a good measure of accuracy. We all know the touchdown passes are not the best measure of a QB helping his team score. We all know raw yards don’t mean very much at all, and we all know that interceptions are not the only way that a QB can hurt his team.

Considering Passer Rating has four terms, let’s fix each individually, beginning with completion percentage:

To fix this factor of the equation, we must first come up with a better measure of accuracy than raw completion percentage to avoid our formula being built on garbage metrics and therefore giving garbage results (a more common statistical problem than you’d think). Readers here obviously know this new accuracy measure is going to be CPOE, which stands for Completion Percentage Over Expected, which assigns an Expected Completion Percentage to each pass based on several factors (depth, direction, down and distance, etc.) and compares the QB’s actual completion percentage with it. This helps weed out high completion percentages based on really easy throws from high completion percentages based on elite QB talent.

Using CPOE as my accuracy measure restricts this stat to only being used from 2006 onwards (throw depths were not tracked before then), but honestly this is a stat for the new millennium anyways. The original Passer Rating gets better and better at its job the further back in time you go, so I don’t think our new alternative only coming online in 2006 makes that big a difference.

To scale this the same, I need a CPOE of zero (zero points above expected is average by default) to correspond with a value of one in my new formula, and for the outstanding portion, I have averaged out the top CPOE in the NFL every year, and found the most accurate QB in the NFL generally completes seven percent more passes than he should. Therefore, a CPOE of seven flat should result in a factor score of two.

Making both these things true at once yields the following accuracy factor:

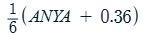

This will need to be bounded at zero, as factors less than zero in passer rating are not allowed, and CPOE figures less than -7 do occasionally pop up, but once that happens I believe that this will be a much better measure of accuracy in my new formula than the raw completion percentage used in the original Passer Rating. This moves us onto the second factor, the yardage factor:

Yards are tough to account for. Not many stats scale themselves in terms of yards anymore. I was originally going to use Football Outsiders’ DVOA for this (Yards Above Replacement converted into a per attempt figure), but that statistic being paywalled now would violate the spirit of what Passer Rating was trying to do, as not everybody would be able to calculate this themselves. Therefore, I’m going to stick to the tried and true Adjusted Net Yards Per Attempt (ANY/A).

This is simply a yards per attempt stat that bonuses some for throwing touchdowns, and penalises some for getting sacked or throwing interceptions. I do run the garbage in garbage out risk from before by electing to bake in a stat that also overrates the importance of turning the ball over (like ANY/A does), but when looking for a stat scaled in yards there’s only so much good you can do.

However, I do like how the original Passer Rating formulation really downplays the importance of raw yardage, so I’m going to keep that aspect here. I will once again scale this factor so the best ANY/A ever posted (Peyton Manning’s 9.78 in 2004) will score just 1.66, and three Adjusted Net Yards Per Attempt will score 0.55, to correspond with the lowest yards per attempt score ever posted in the original Passer Rating Formula. Making those things both be true results in the following formulation:

This means to score a one on this component factor requires 5.64 ANY/A, which is close enough to NFL average to not make this a total sham. Moving onto the third factor. Touchdown Passes:

To fix this factor requires a more accurate understanding on how a QB’s contribution impacts his team scoring points. Thankfully, EPA/Play is designed specifically for such a purpose. The whole point of this statistic is to quantify a QB’s production based on the amount of points contributed to his team’s score, over and above the expected level. I have a whole article about this if you wish to learn more.

Since EPA is once again an ‘above expected’ stat, the average is again going to be around zero, but in this case, it’s a little funky. Due to some statistical quirks that are not worth the time it would take to explain them, average EPA/Play for a QB is about 0.04, so this is the value that will correspond to one in the factor score. Using the same averaging method as with CPOE, a typical top of the NFL EPA/Play is about 0.322. Therefore, this result will create a factor score of two. Both of these conditions holding creates the following factor:

This must also be bounded at zero, as EPA/Play values less than -0.24 are possible, but with that slight modification we move to the granddaddy of them all, the interception factor:

This is a tough nut to crack, as this factor aims to punish bad play, but in order to do so we need a more all-encompassing stat that records in a more accurate and holistic way how good QBs are at avoiding negative plays. Such a stat does not publicly exist. Thankfully, I’ve invented one, and since I’ve made the formula public and it uses publicly available data, it does fit the criteria for Passer Rating.

The stat is called Turnover Equivalent Plays (TEP), and it combines actual turnovers, sacks, and especially costly incompletions into one number that is a better evaluation of how many mistakes a QB makes than looking at their turnovers alone. Read my article introducing it to learn more.

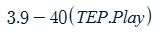

An average QB will commit a Turnover Equivalent Play on about 7.2 percent of all touches. This will result in a factor score of one. The top QB in the NFL at avoiding negative plays will commit a TEP on roughly 4.7 percent of all plays (Turnover Equivalent Plays are bad, so less is better). Therefore, a 4.7 TEP rate will end in a factor score of two. Holding both of these things results in the following formulation:

This stat must also be bounded at zero, because TEPs on ten percent of touches can be done by a really bad player. It also comes close to needing to be bounded at the top at 2.375 (like the factors are for real Passer Rating), but as of yet a TEP rate of just 3.81 percent (the upper bound) has never been achieved, although 2019 Drew Brees and his 3.83 percent got intimidatingly close.

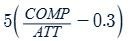

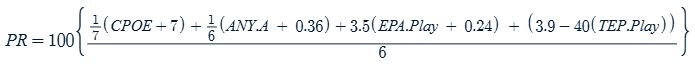

Now that we have our four factors decided, this is the formula for my new and improved version of Passer Rating:

This may look long and complicated, but in reality anybody with a basic office calculator can plug in all these numbers, just like the original PR, and it’s on the exact same scale, meaning we don’t need to change our interpretation of what number makes a good Passer Rating. The only changes my version makes is that now it does include the possibility of non-passing outcomes (like sacks and rushing attempts), and also properly accounts for the reality that turnovers are not the worst thing in the world for an offence, as long as everything else is going well.

The one thing we must keep in mind is that the averages I’ve set for this new Passer Rating in each of the four components are actually correct, and not far too low like they are in the official version. Therefore, it’s dramatically less easy to be above average at something, which causes scores in general to be lower. In my version, a league average QB is roughly a 74, compared to 2023 where a league average QB is roughly a 92.

So now that we’ve got this fancy new statistic, let’s take it for a spin.

I’m going to begin with Brock Purdy, who is a player that plays in a way the original Passer Rating really likes (mid interception rate, but top of the line completion percentage), and therefore ended the 2023 season with a seriously impressive 113, but how impressive is it to score so highly on such a flawed statistic? Let’s see how he does on the new and improved version. Here are Brock’s component numbers from 2023:

CPOE: 5.4

ANY/A: 9.01

EPA/Play: 0.338

TEP/Play: 6.9 percent

Plug these numbers into the new and improved formula, and Brock Purdy has a Passer Rating of 108 flat. This is still by far the top of the NFL, winning by four full points over second place Dak Prescott and his 103.9 on the new leaderboard, and once again considering my factors are actually scaled correctly, those are the only two QBs over 100 in 2023.

This was merely an exercise to prove that you can play in a way that both the original (which loves high completion percentage and low interception rates above all else) and my new (which loves actual accuracy and scoring lots of points) version of Passer Rating both love, because the top two in each are the same two people, but let’s get into what my new stat is really designed to do, starting with the man who probably more than anybody else in NFL history, Passer Rating was designed to hate.

Josh Allen.

In 2023, Josh was the league average (16th out of 32 qualified starters) according to the original Passer Rating, with a 92.2. This is because it hates his style of passing, which entails really difficult throws which lead to low completion percentages, lots of interceptions, but also tons and tons of points for the Bills. In addition, Passer Rating (on purpose) entirely ignores what in my opinion are Josh’s most important skills: his prodigious ability to avoid being sacked, and how electric he is running the football. What people think Mike Vick was is what Josh Allen actually is, and Passer Rating doesn’t care about a bit of it. Thankfully, my version does. Let’s look at his 2023 component stats:

CPOE: 5 flat

ANY/A: 6.51

EPA/Play: 0.193

TEP Rate: 6.3 percent

Plugging them into the new formula vaults Josh Allen all the way from 16th to third in the 2023 Passer Rating rankings, with a 95.8. Perhaps not surprisingly, Josh is the one of only two players (Jalen Hurts) to actually improve his 2023 score with the transition to my new, much more difficult to impress, formula. Dak Prescott came close, only losing about two points, but most lost ten points or more in the transition.

Nobody loses more points in the 2023 transition than CJ Stroud, who is going to be my final example of the day. Despite his mediocre 63.9 completion percentage, the original Passer Rating absolutely adores his one percent interception rate, and is impressed with his 8.2 Yards per Attempt, but with the new formula, this all changes.

I can agree that CJ Stroud has mediocre pass accuracy, but what the original Passer Rating misses is that CJ is in fact not all that great at avoiding negative plays, with his TEP Rate landing exactly average at 7.2 percent, which is because of his propensity to take sacks all the time. Let’s get to his component numbers:

CPOE: 0.2

ANY/A: 7.47

EPA/Play: 0.124

TEP Rate: 7.2 percent

Plugging these all into the formula sees CJ Stroud rated 76.6 by the new formula, losing an unimaginable 24.2 points of rating, and dropping from sixth all the way to 18th in the NFL rankings. The removal of priority status from avoiding turnovers really kills CJ’s perception, as this new stat sees him as being mediocre at three of the four component factors, and only being quite good in terms of yardage, by far the least important thing to be good at.

As I said before, most players dropped at least ten points simply due to the averages actually being scaled correctly now, but nobody dropped this many, with the next closest being a multiway tie with a lot of players all losing 17 points. This just goes to show how hyper-focused on the relatively unimportant skill of avoiding interceptions that Passer Rating is. Once that one stat is replaced with a better one, its golden boy falls all the way to 18th place.

So that’s that. We’ve made a new stat that uses the same scale as passer rating. However, it’s one that takes slightly more extreme stances. The scale is not as tight as the one on the original Passer Rating leaderboard. This is okay, as all it means is that it takes a stand saying bad QBs are bad. For instance, according to my new version, Bailey Zappe’s 2023 Passer Rating was seven (yup, seven).

I would love to solicit naming suggestions for this new statistic. If you have any ideas feel free to comment them.

The one other thing I would like to do is link you to the leaderboard for this new stat so you can see the ranks yourself. I would love to embed one here, but I’m not techy enough to do so, so if you want to know how NFL QBs stack up in this new statistic, click the link below:

That’s it. One more day, one more new stat invented. Hopefully some of you guys can get some good use out of this, as I do think this is a much much better version of the tried and true Passer Rating statistic. Let me know if you have any questions or concerns about how it works.

Thanks so much for reading.